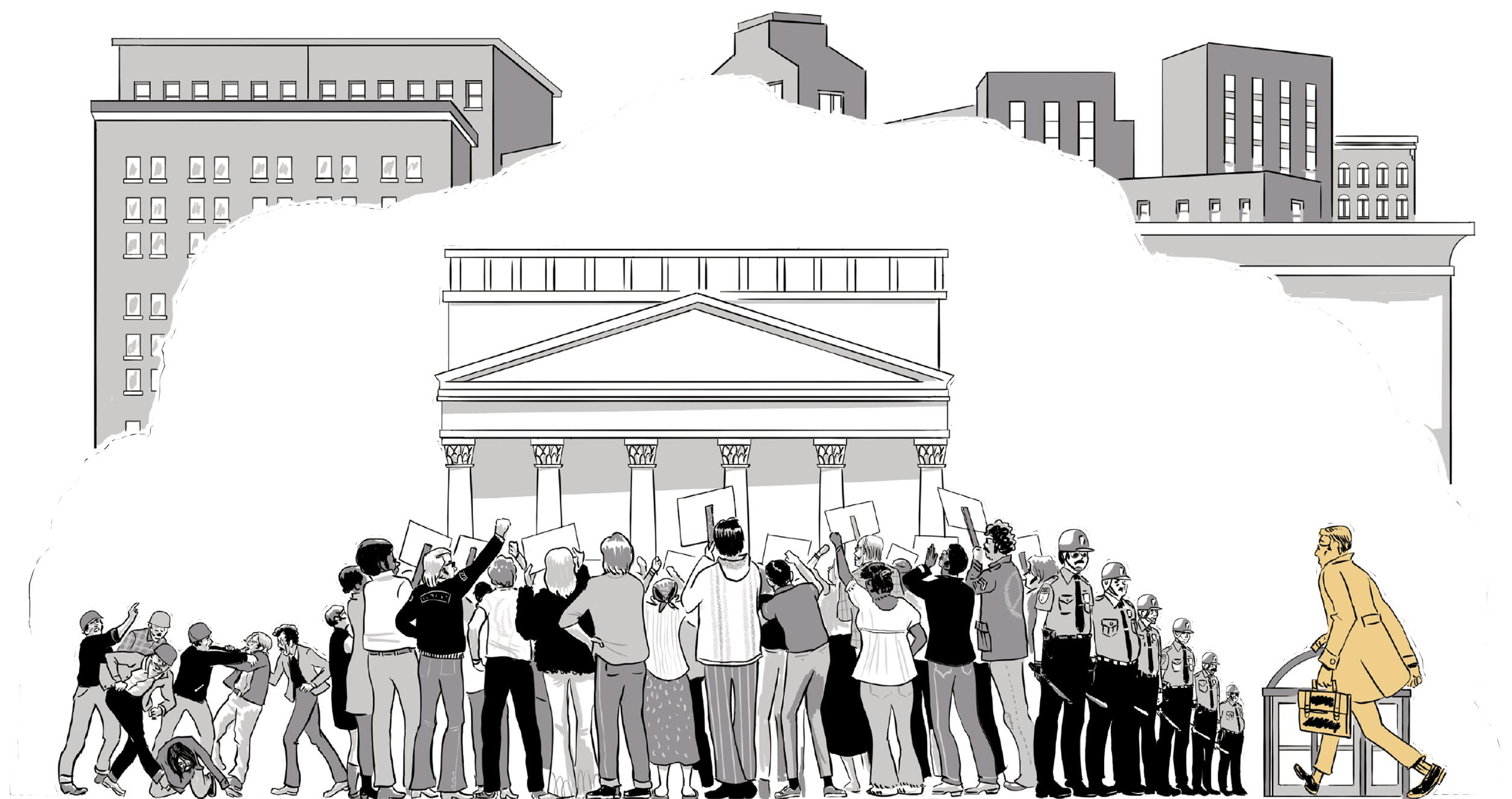

Significant change rarely occurs when things are going well. For obvious reasons, most people would not willingly rock a boat that is sailing comfortably along. But sometimes a new course can be set by a visionary individual who sees an opportunity for radical improvement and steps forward to challenge the status quo.

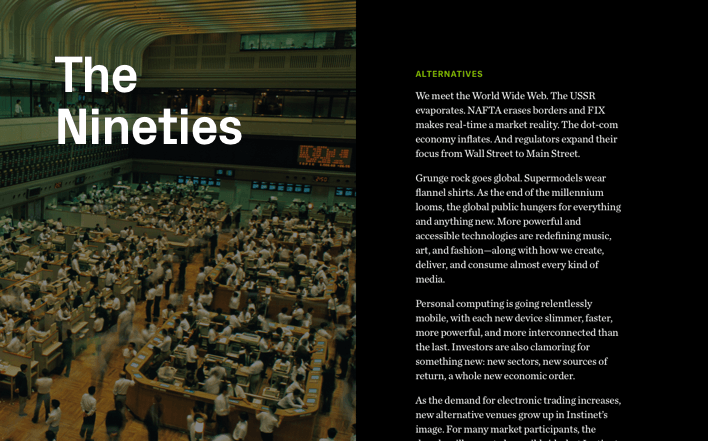

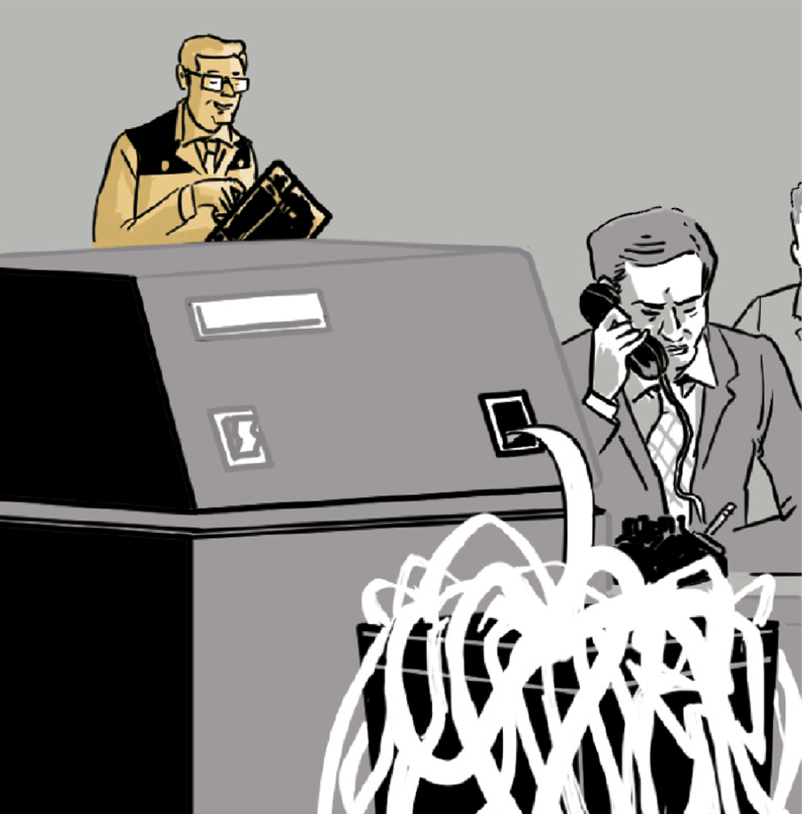

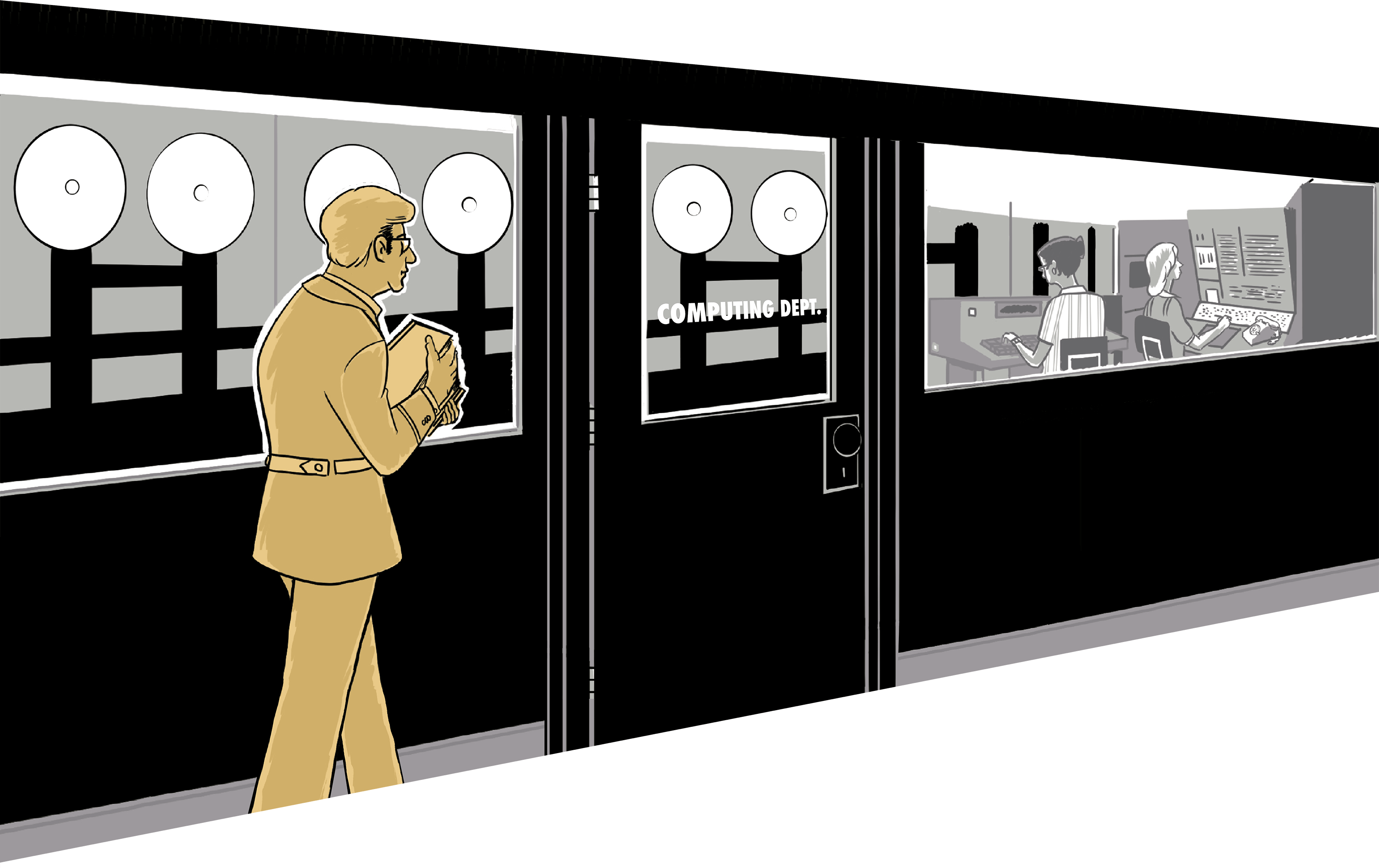

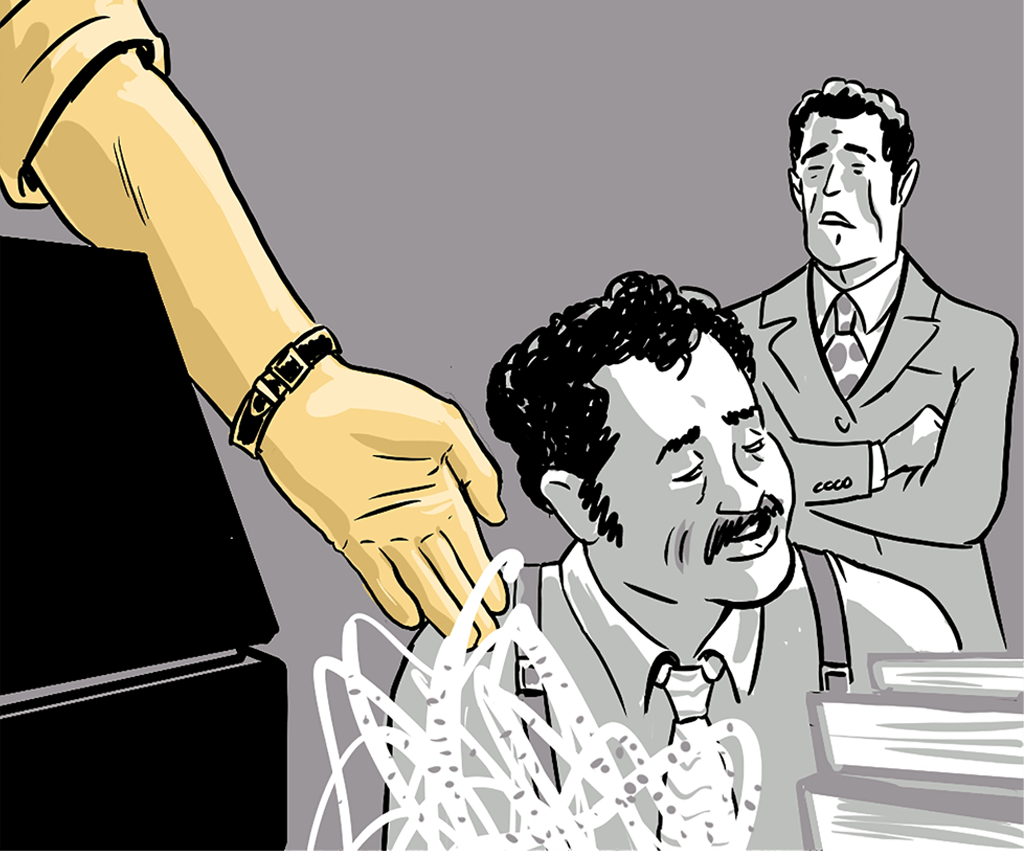

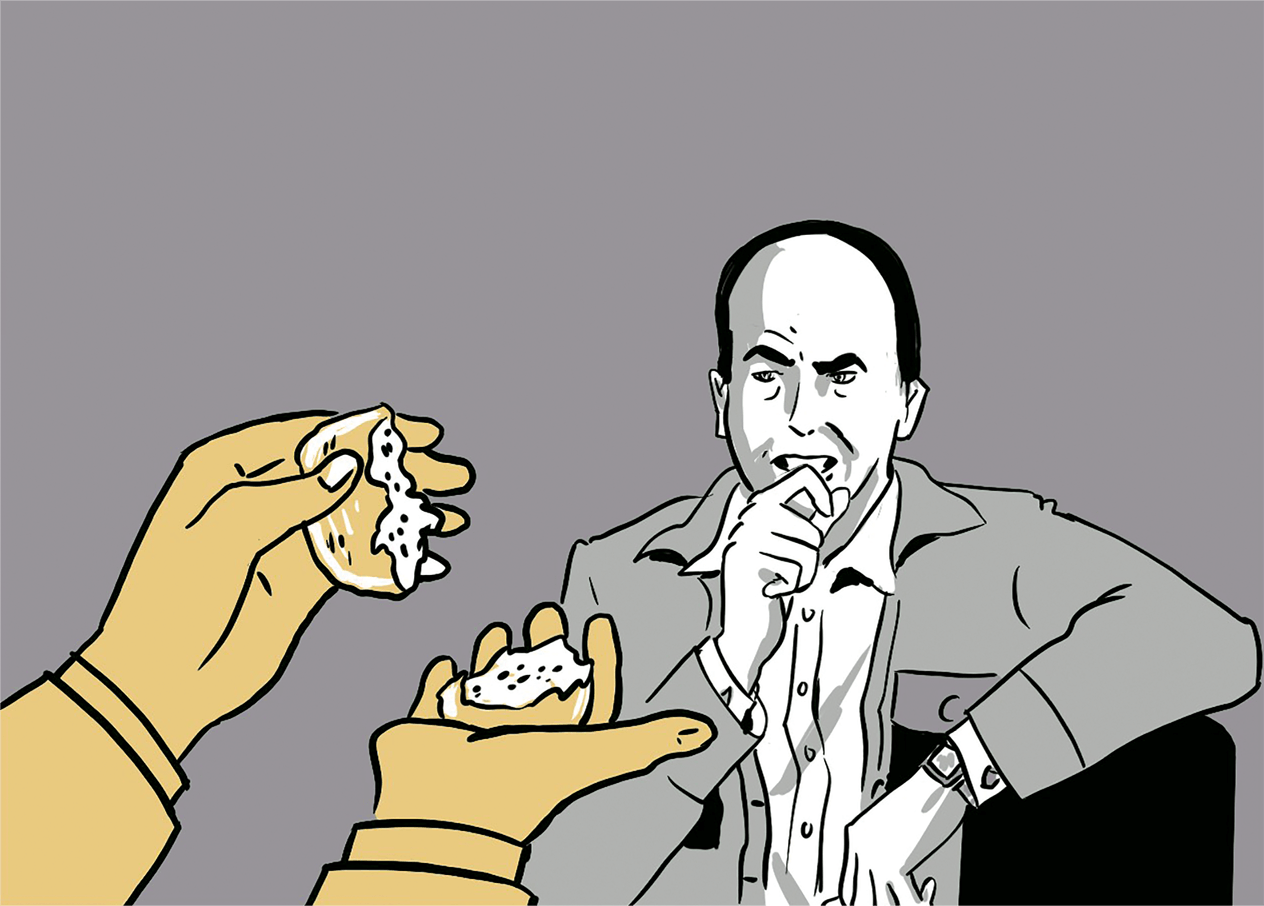

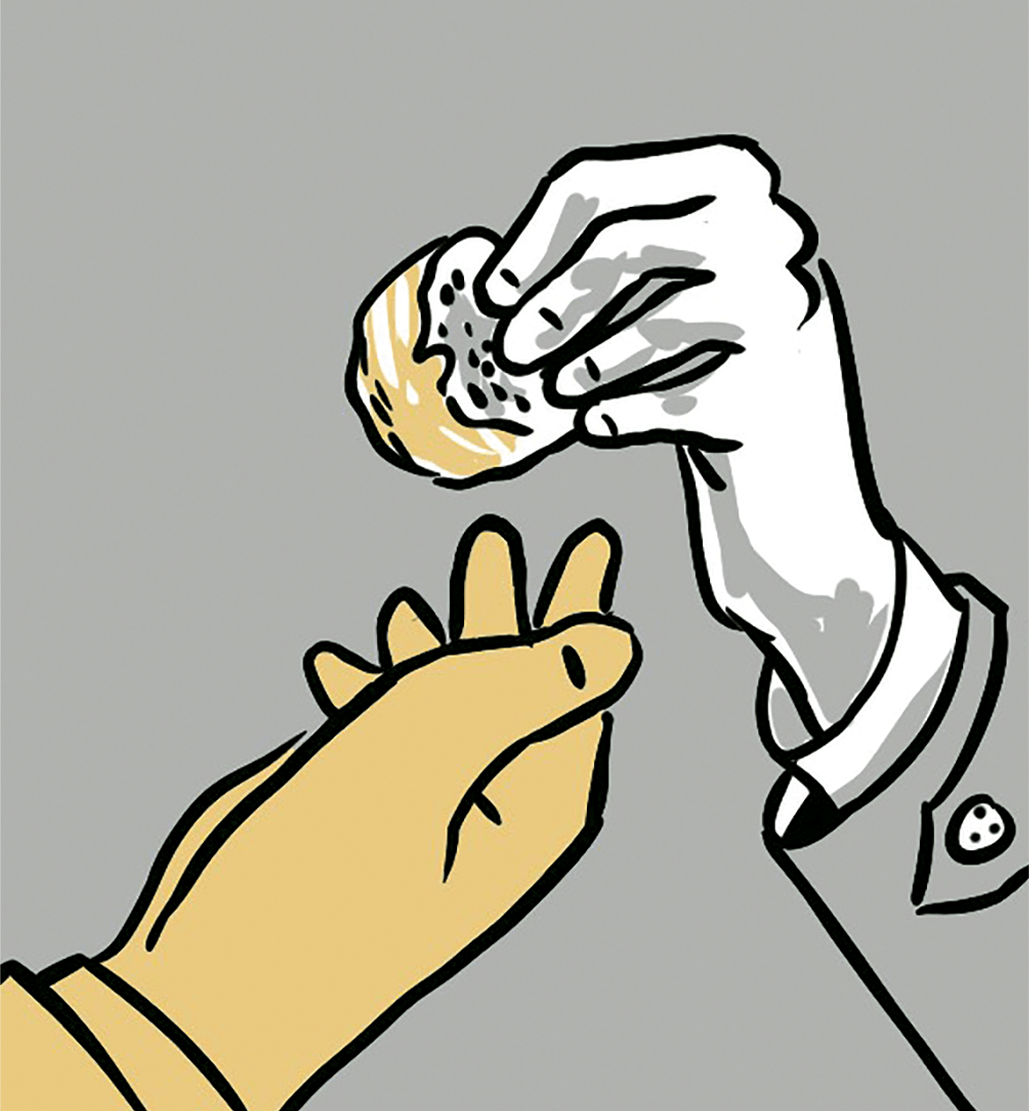

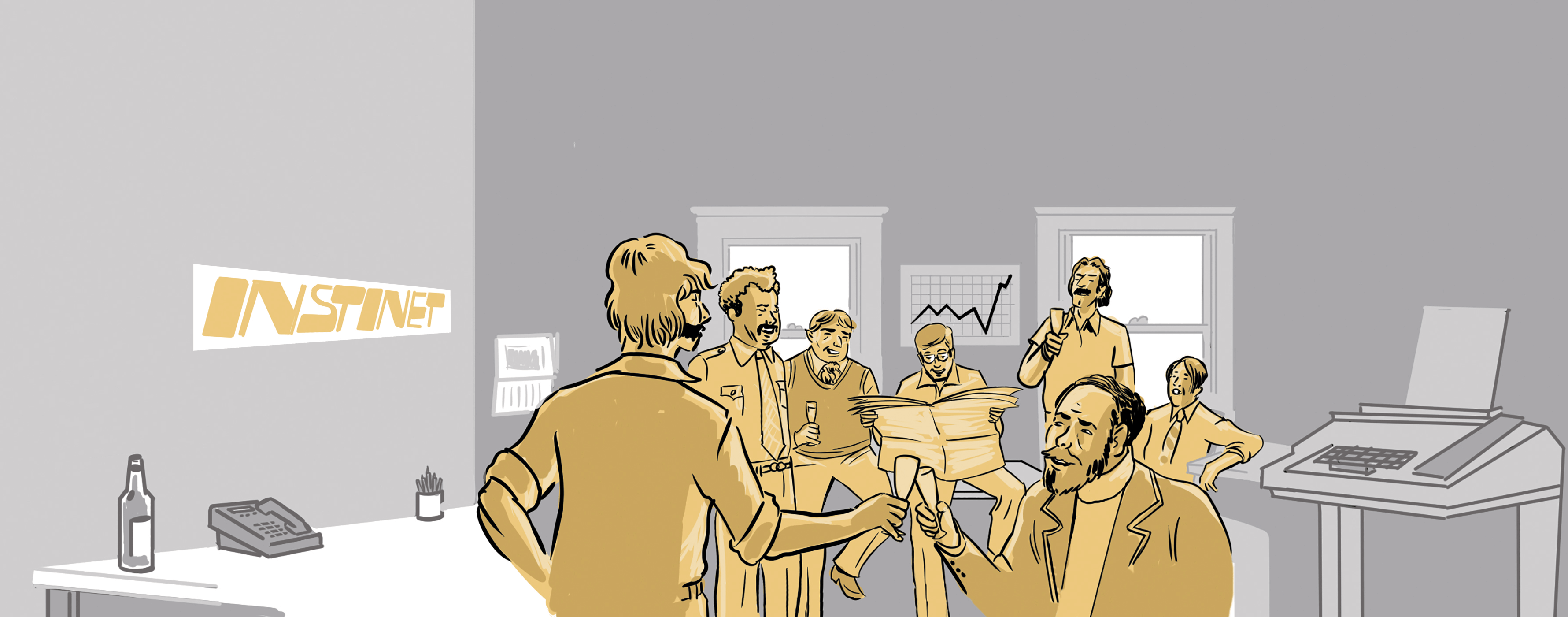

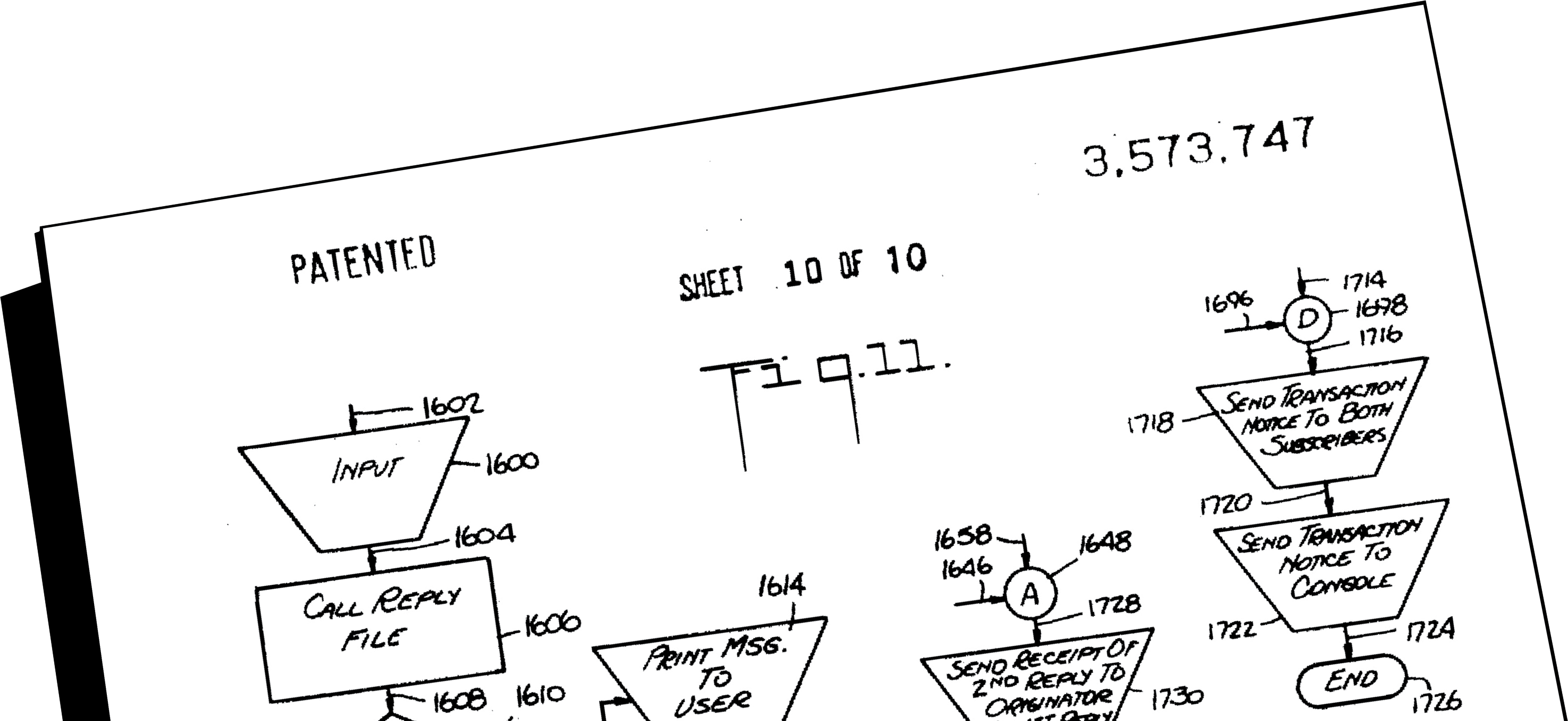

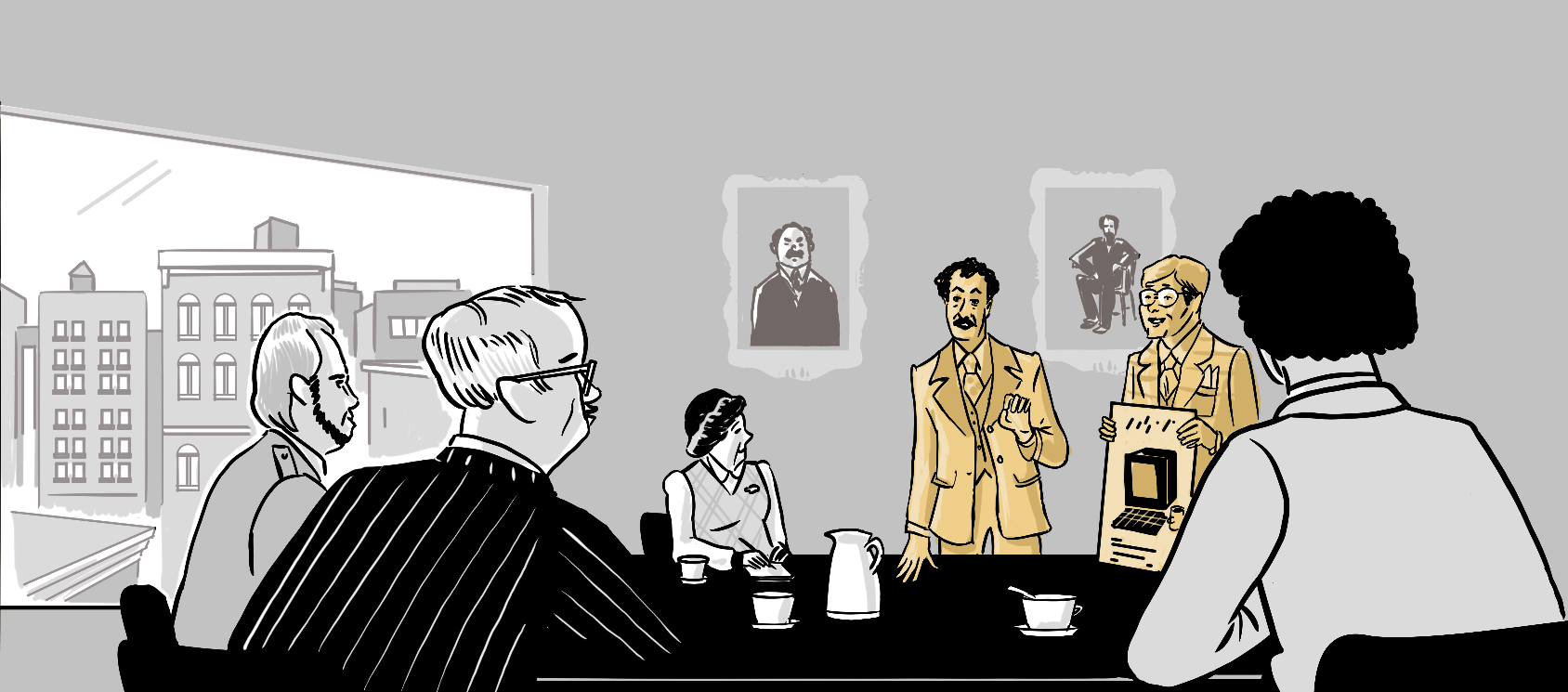

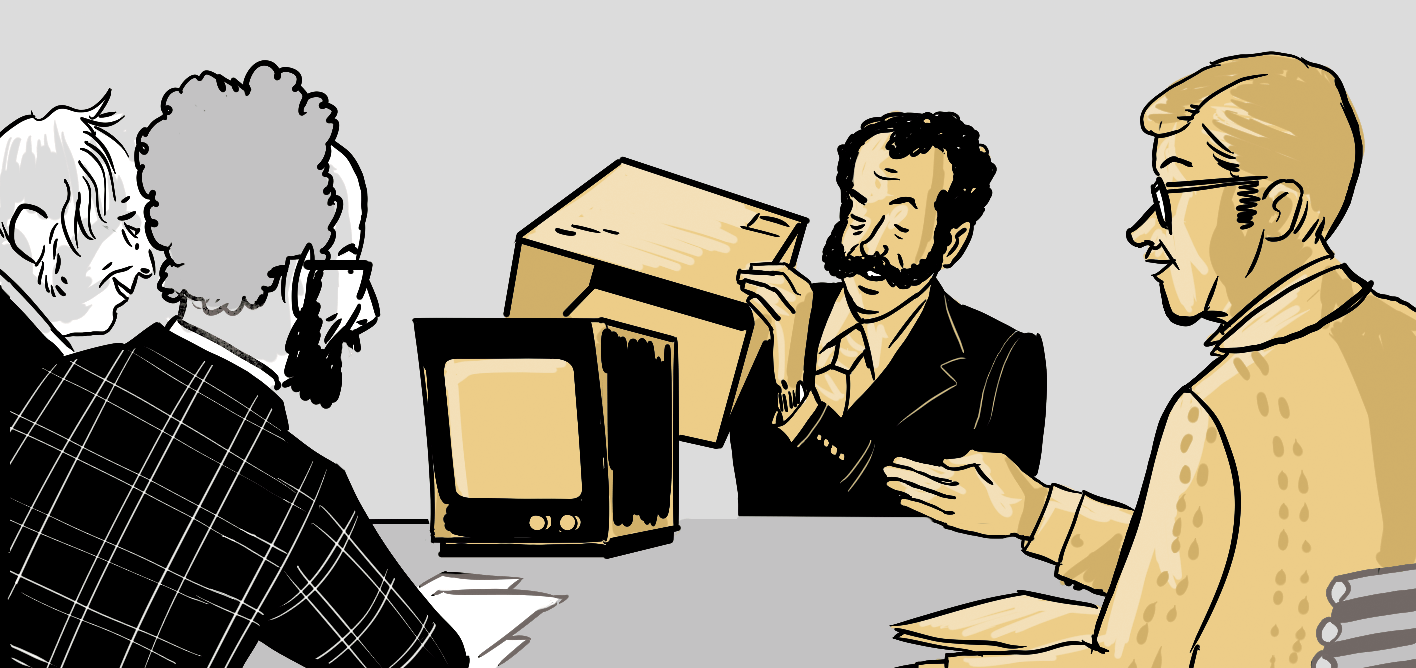

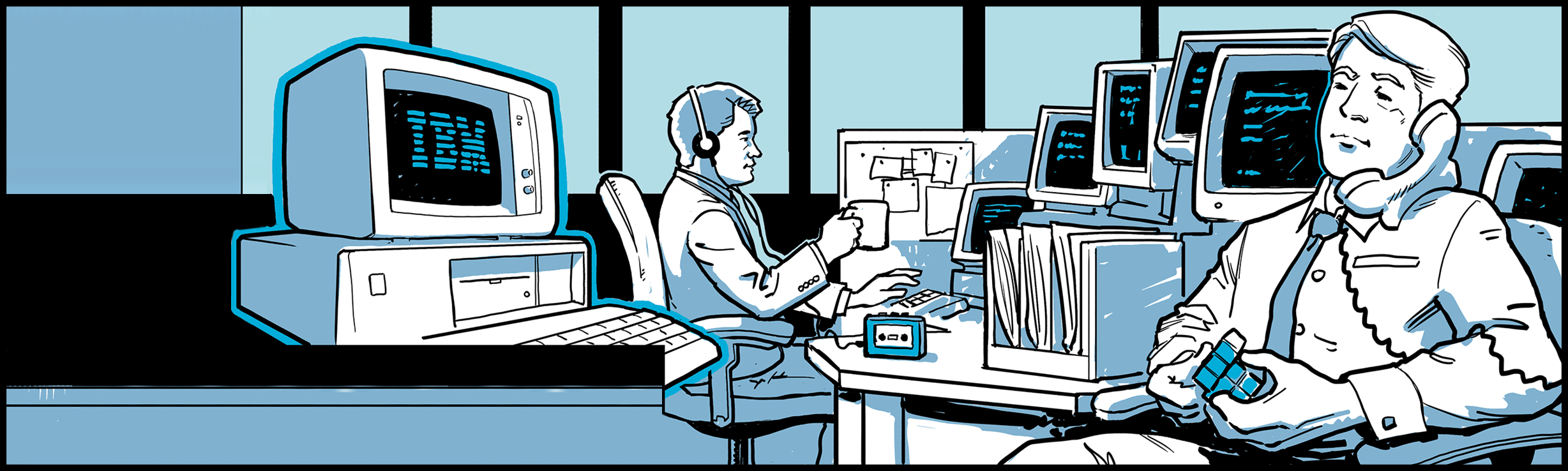

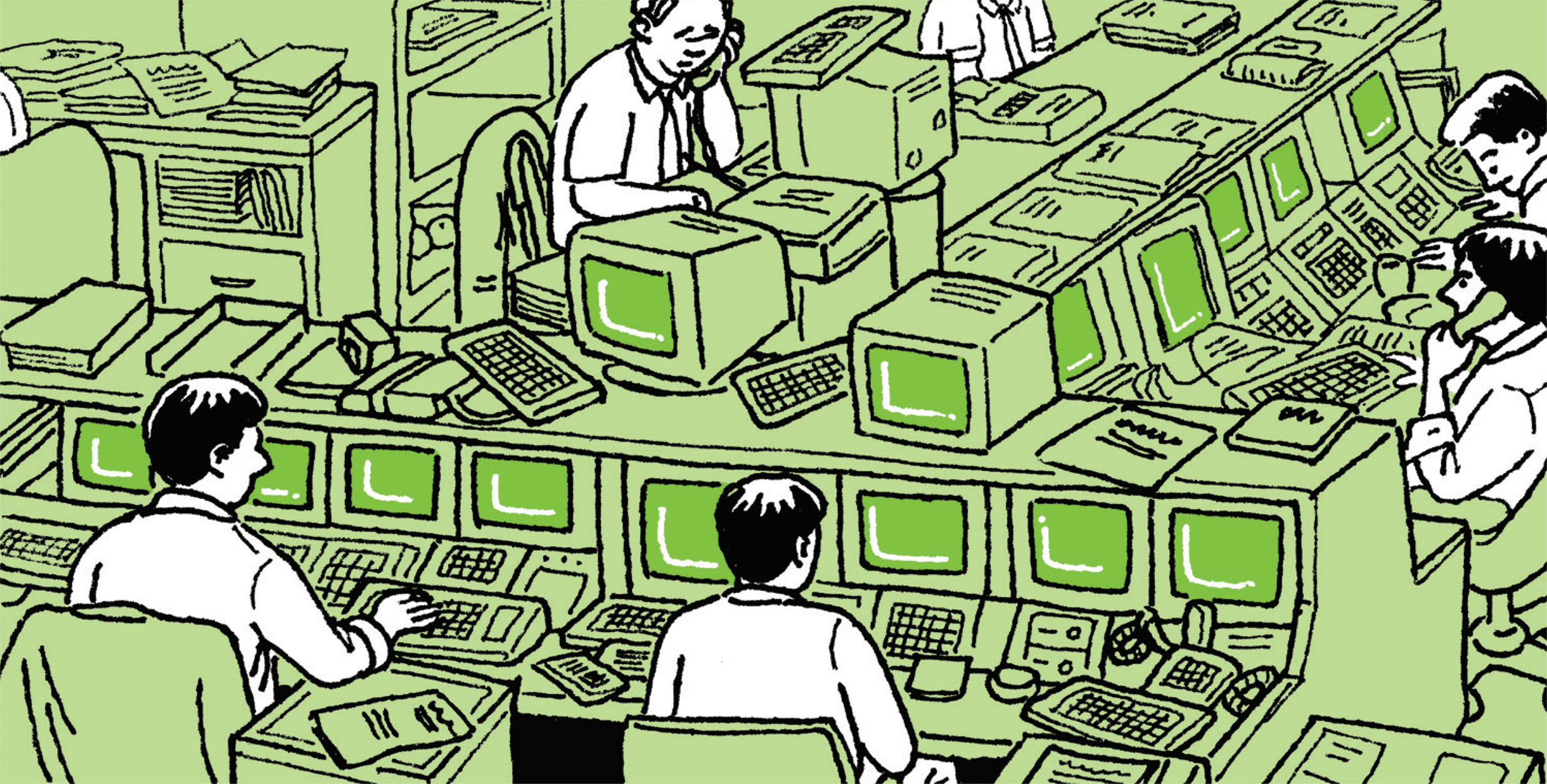

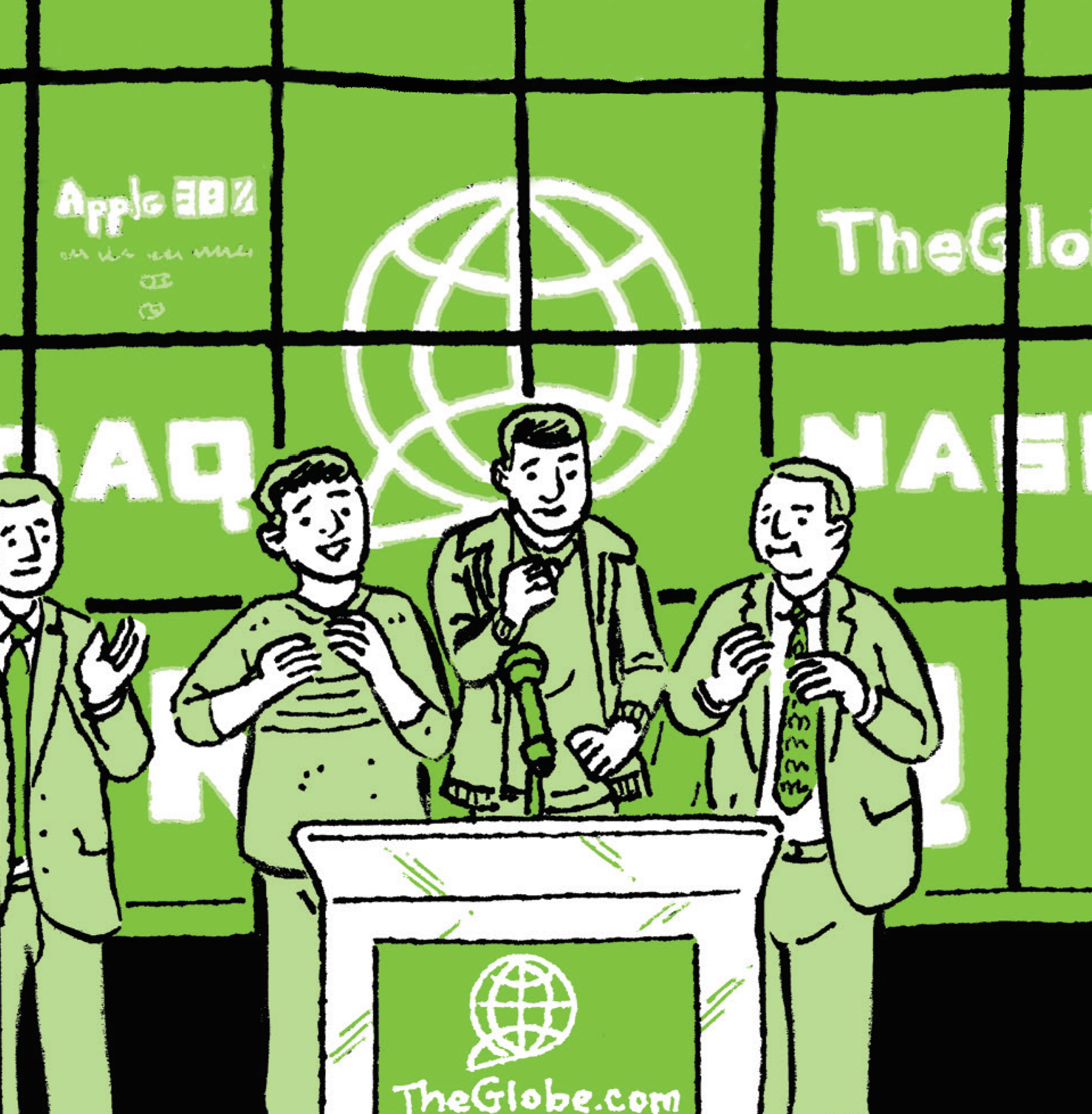

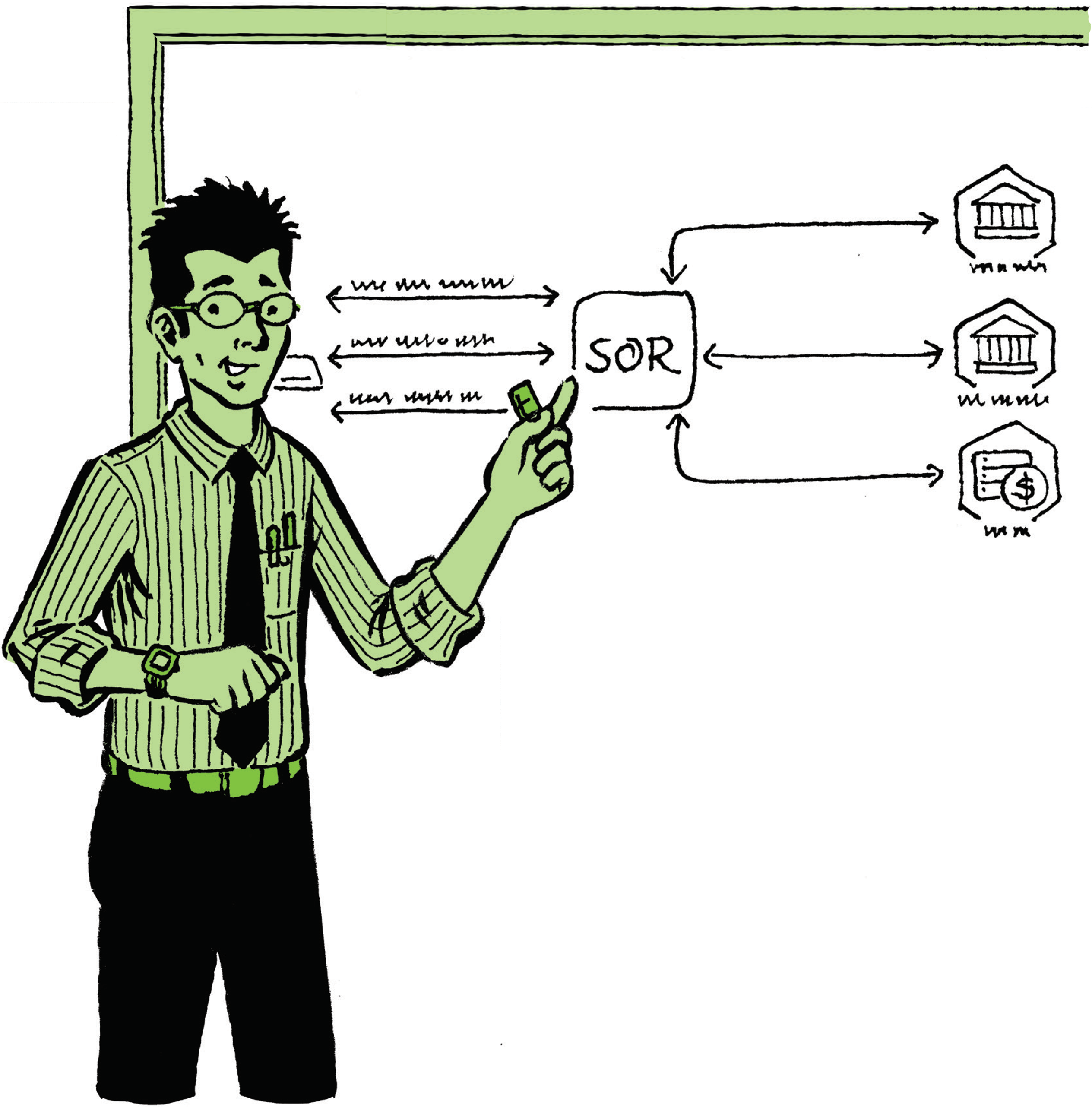

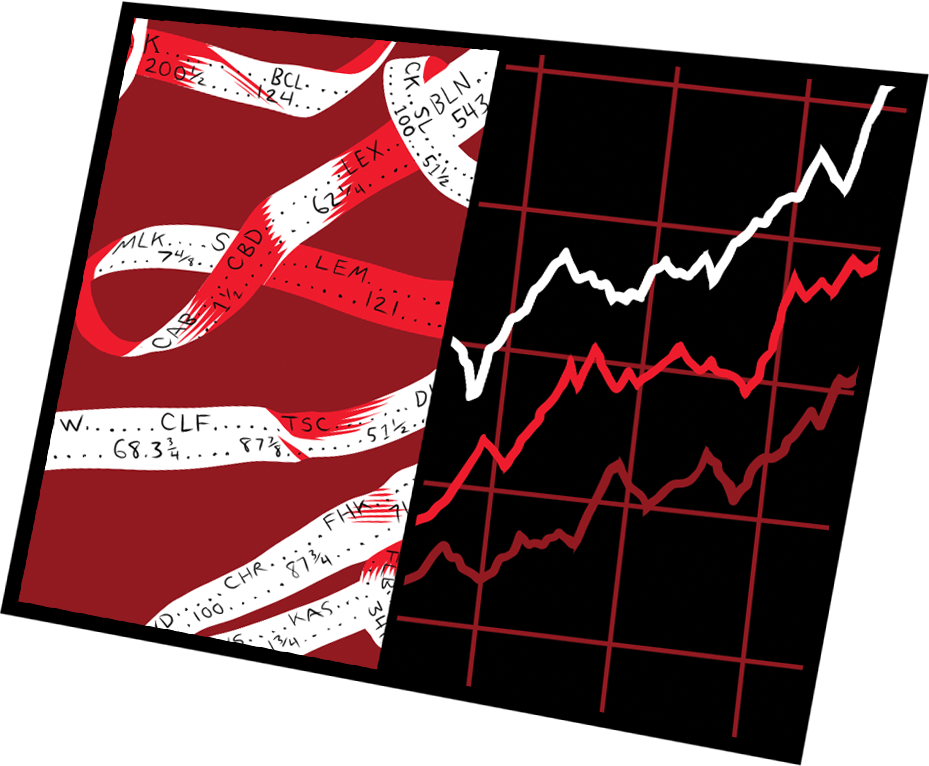

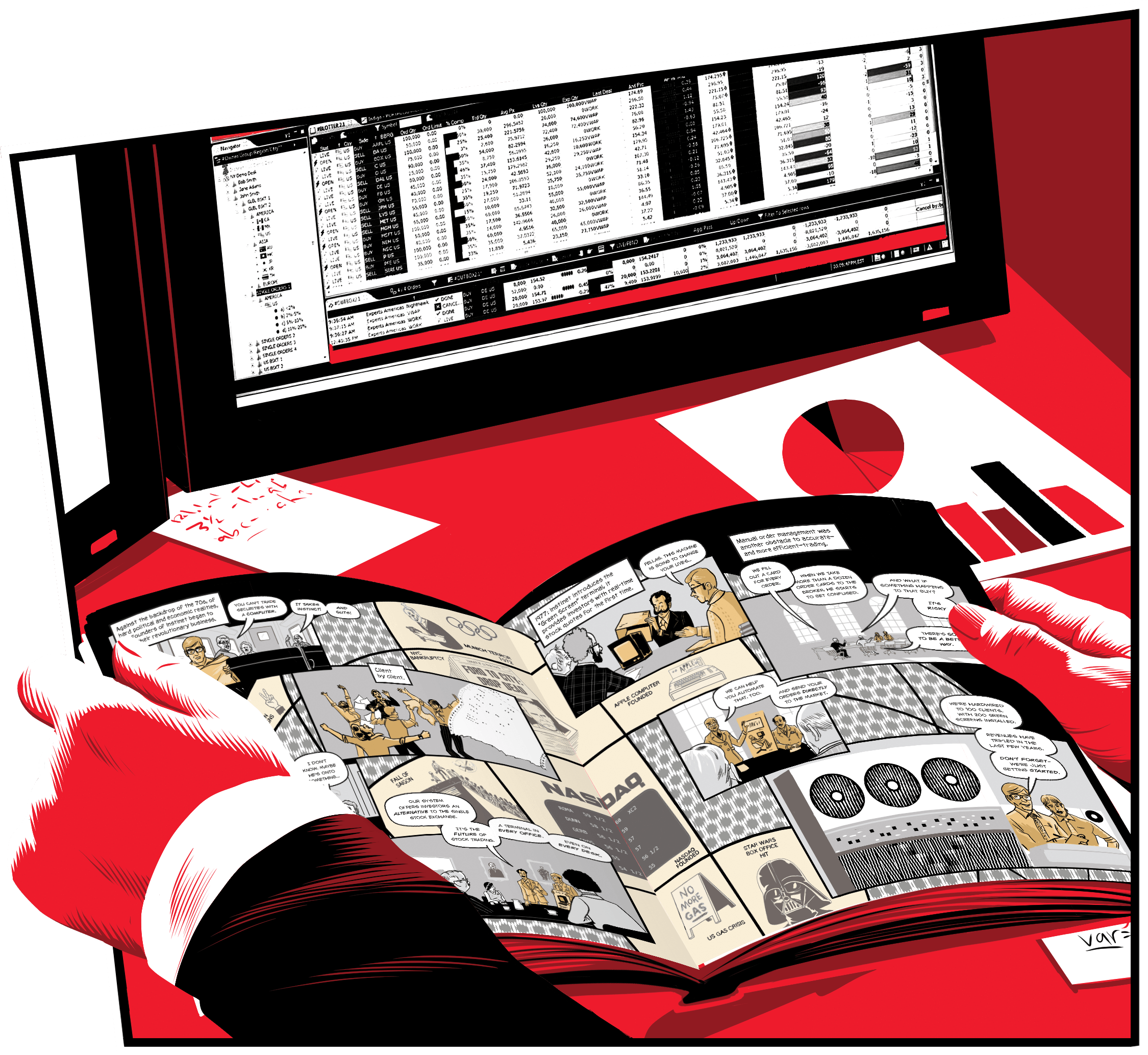

In 1969, Jerome Pustilnik was that visionary individual. He recruited some like-minded partners and started a company called Institutional Networks that would fundamentally change the structure of the financial markets. Their innovation was an electronic network for trading stocks. An alternative to the single, central limit order book that was available to only a few people. It would be a place for investors to connect with each other to execute trades at the best possible price, and for lower cost.

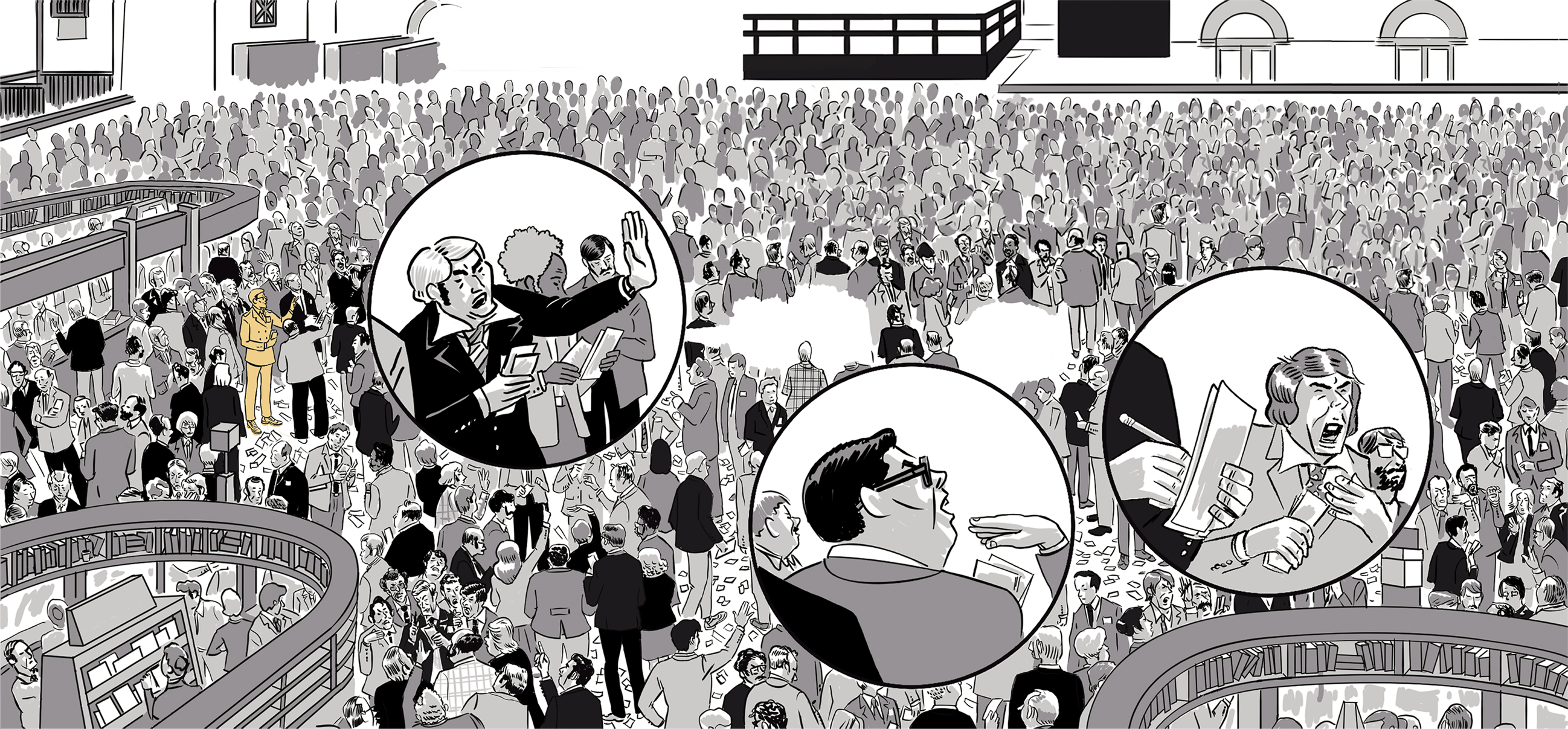

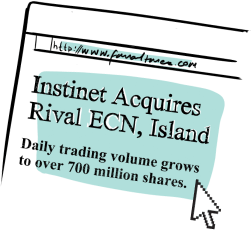

These principles seem basic now, but their introduction was a moment in history that would slowly, inexorably, begin a revolution. Fifty years ago, it was hard to predict the scope of this change, even for the visionaries that were making it happen. And, like most truly fundamental shifts, it took time to catch on. But then, after almost two decades of hard work, Instinet became an overnight success.

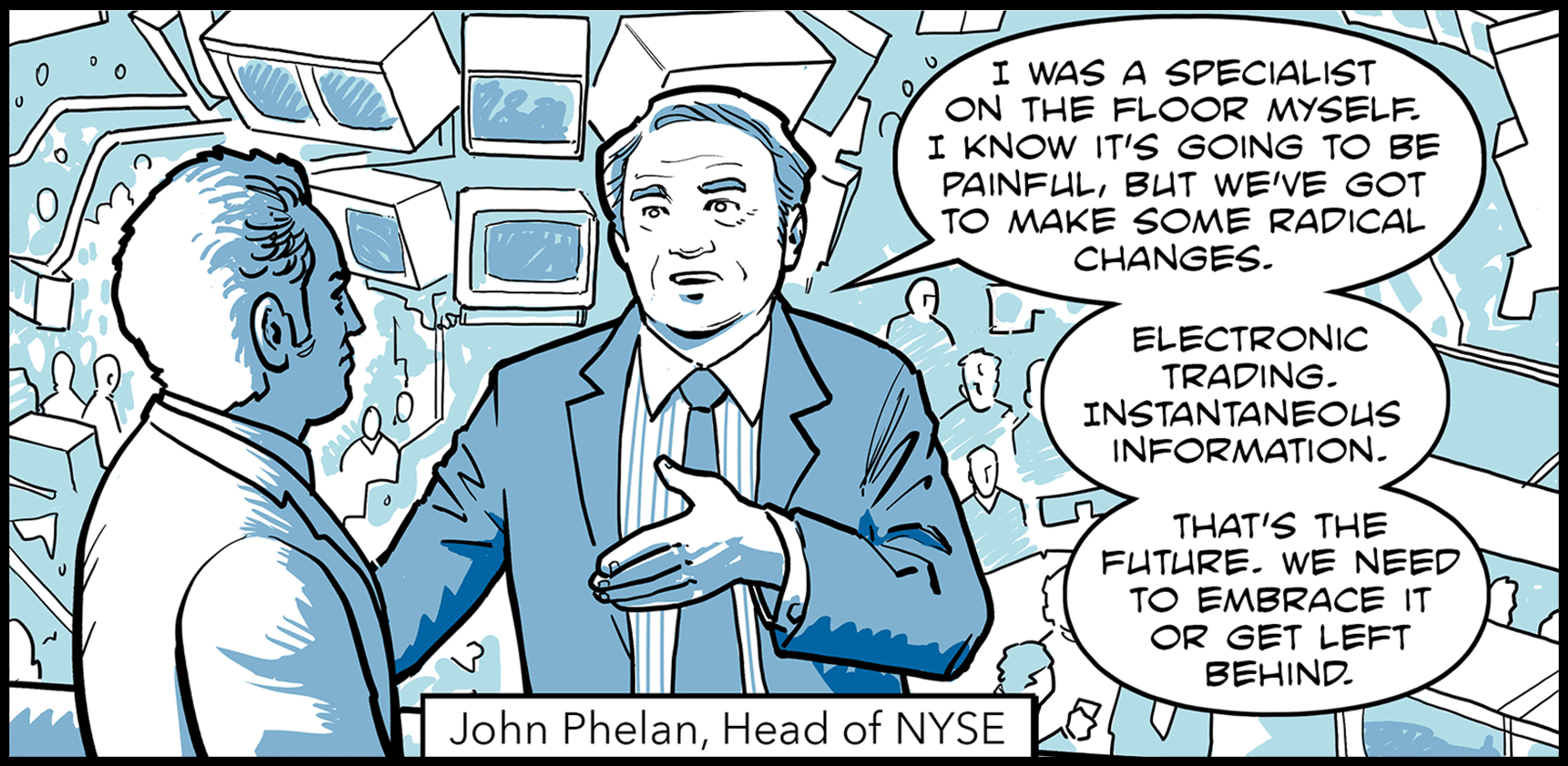

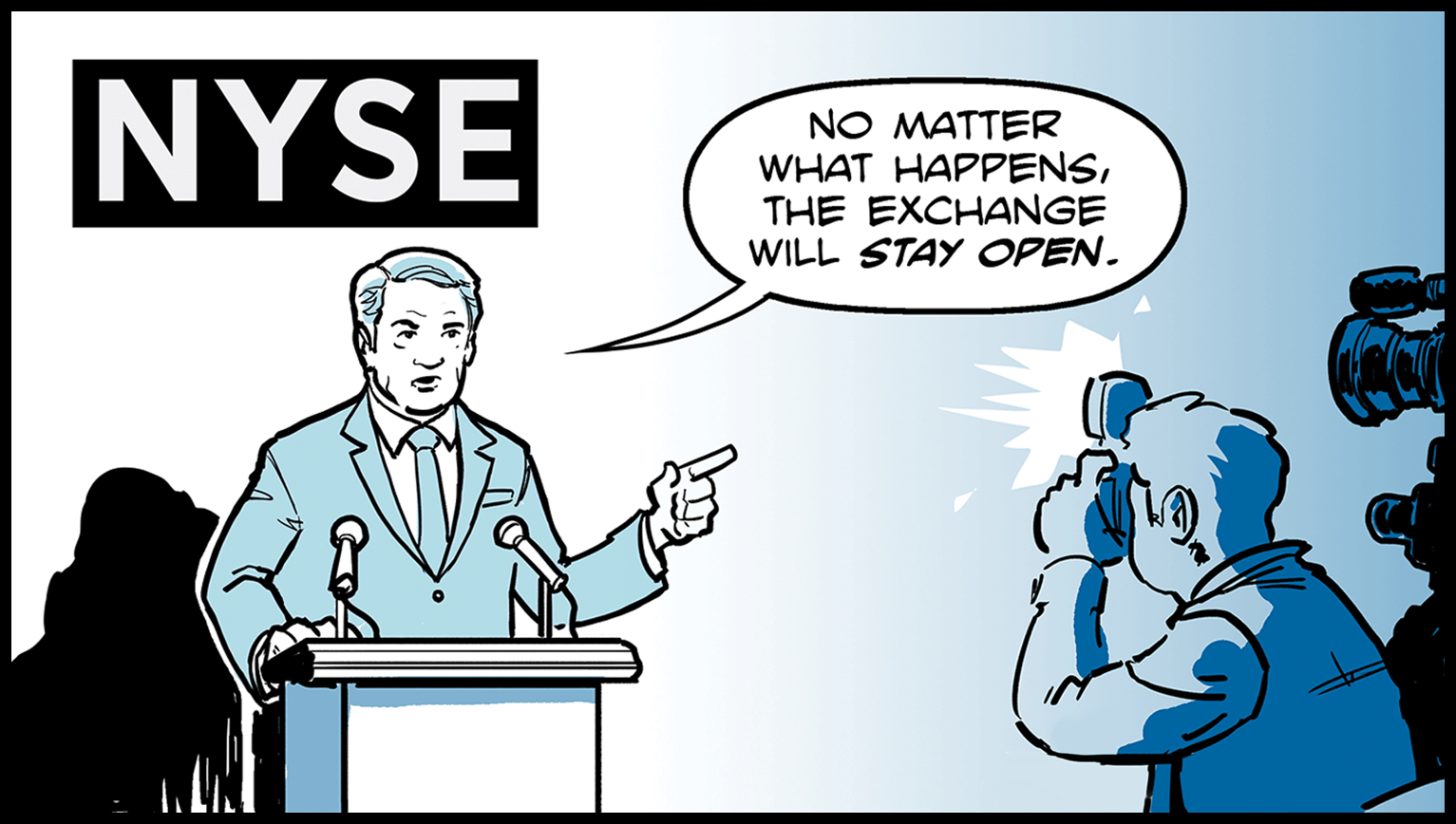

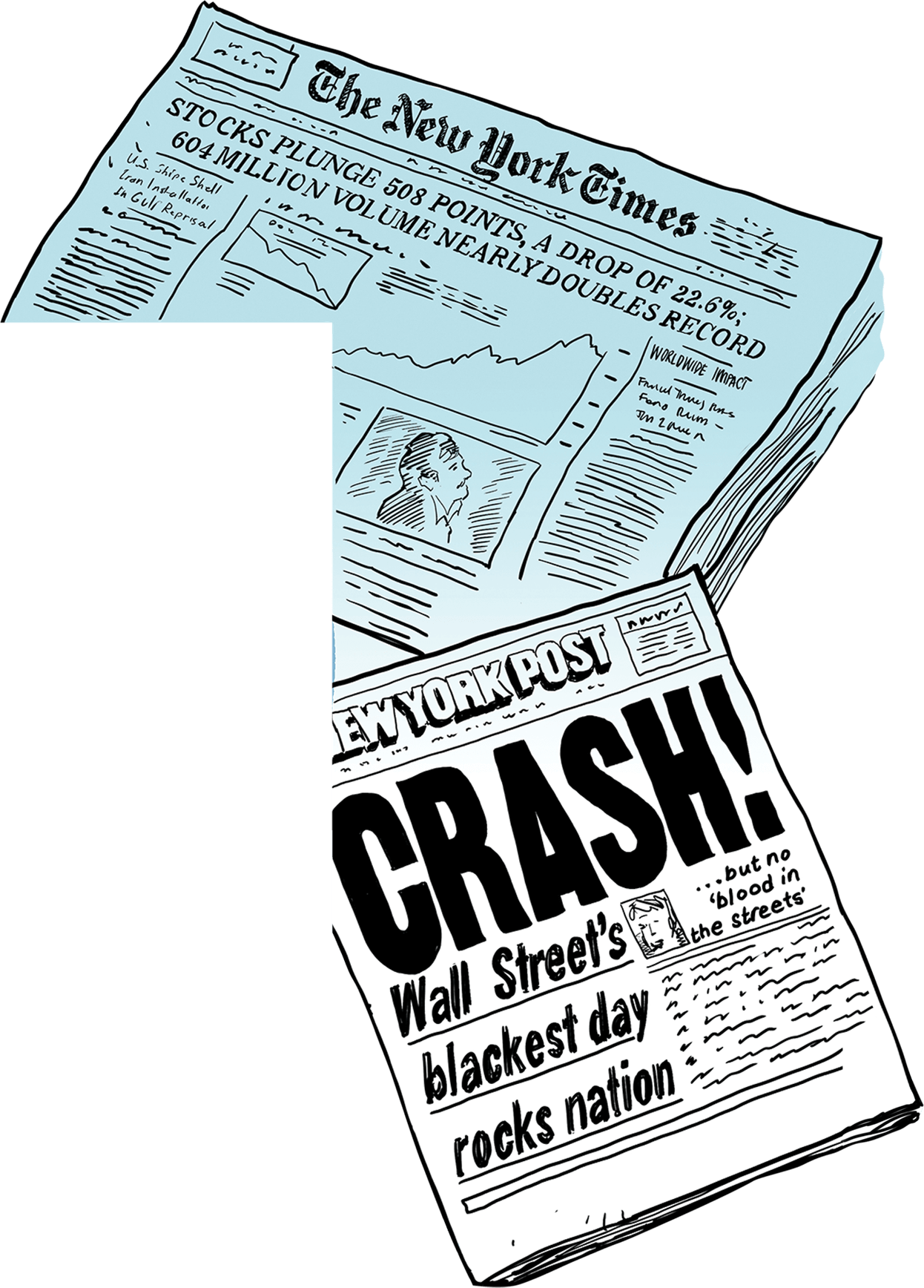

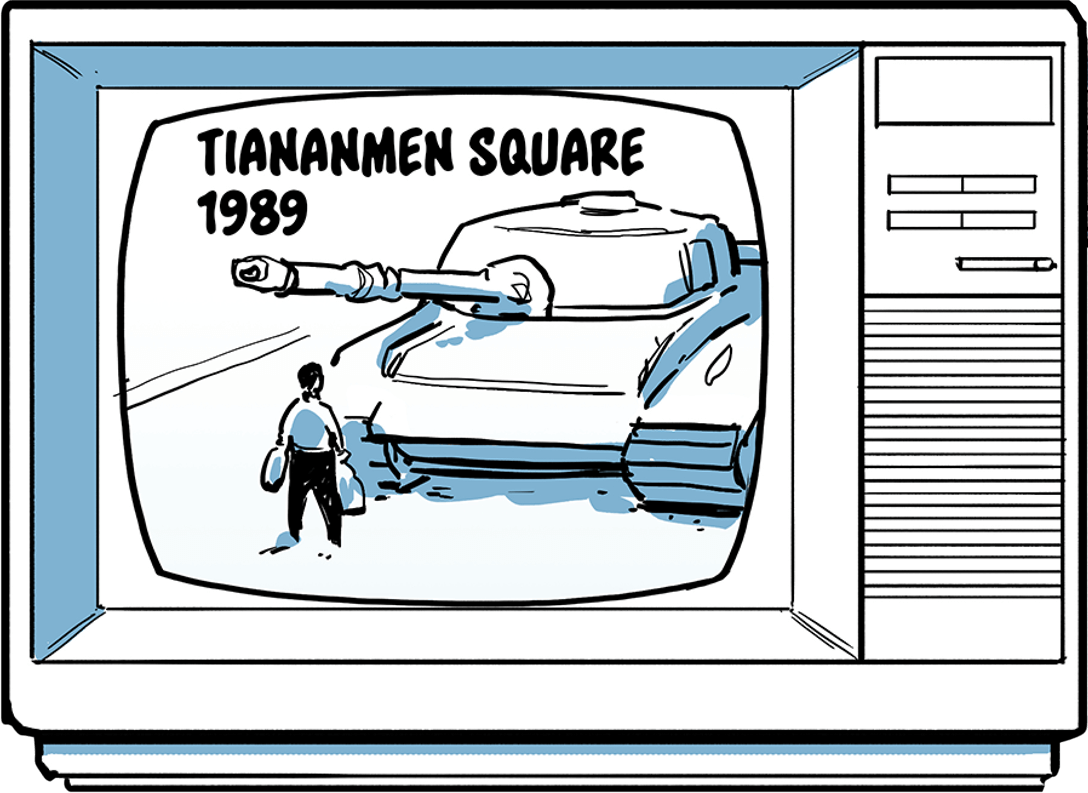

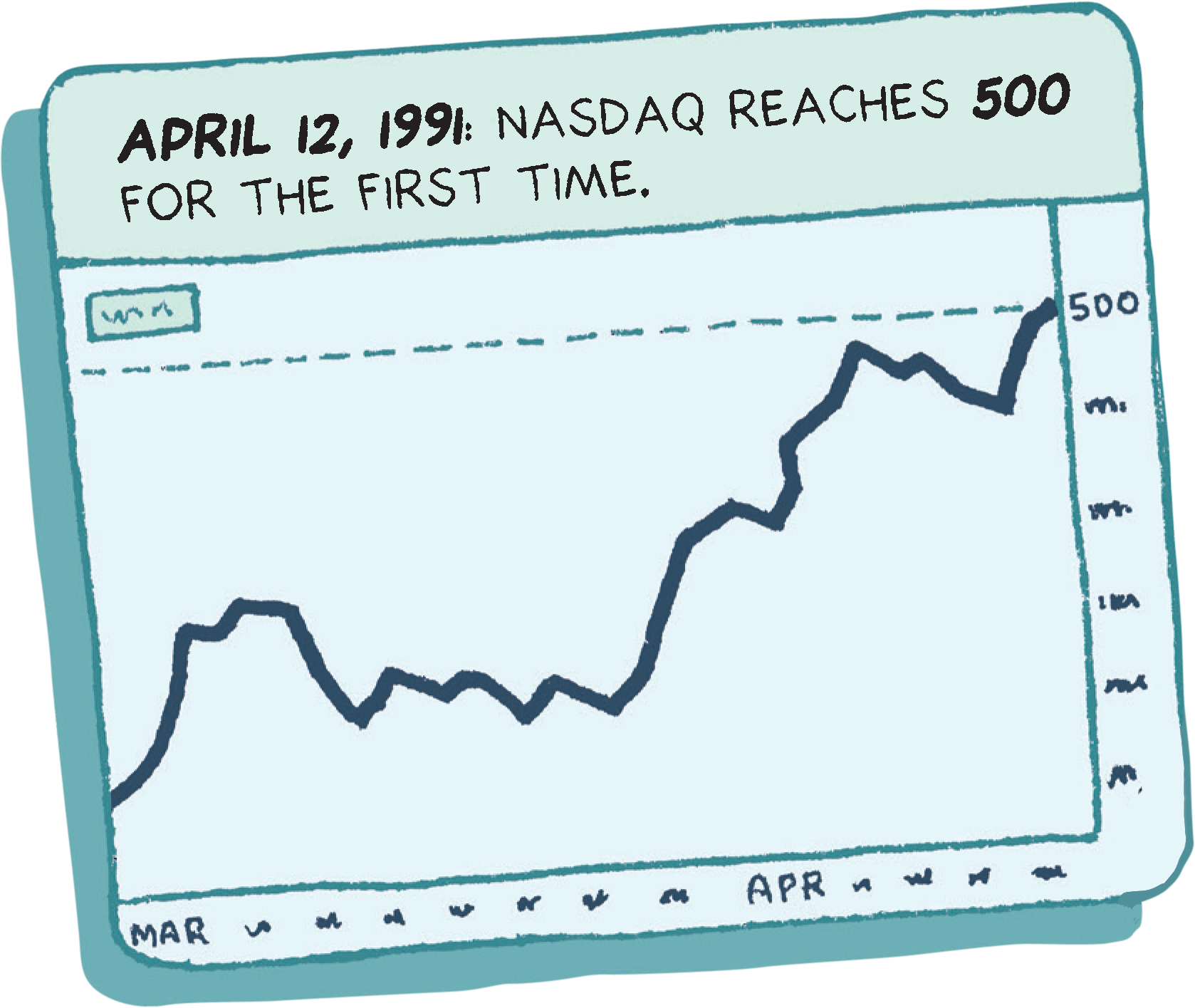

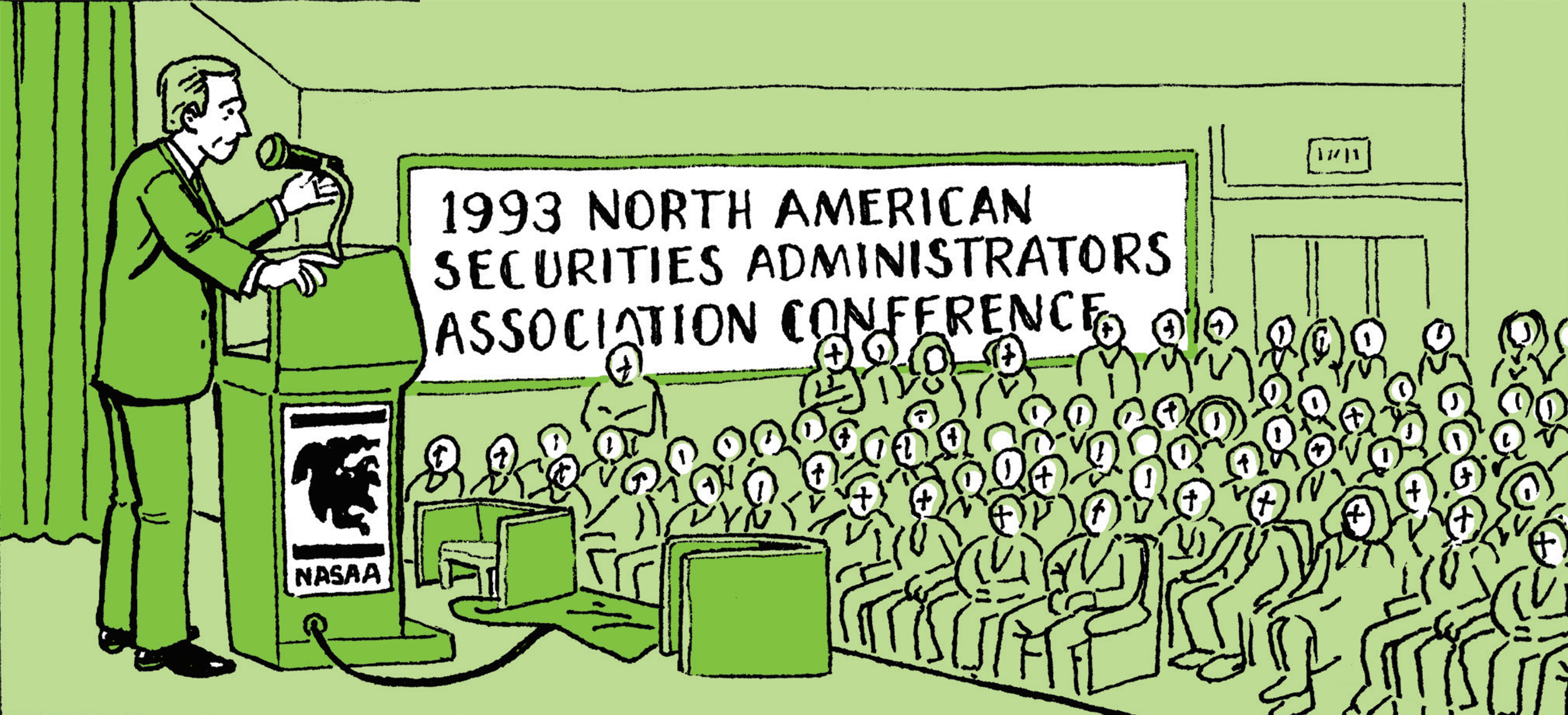

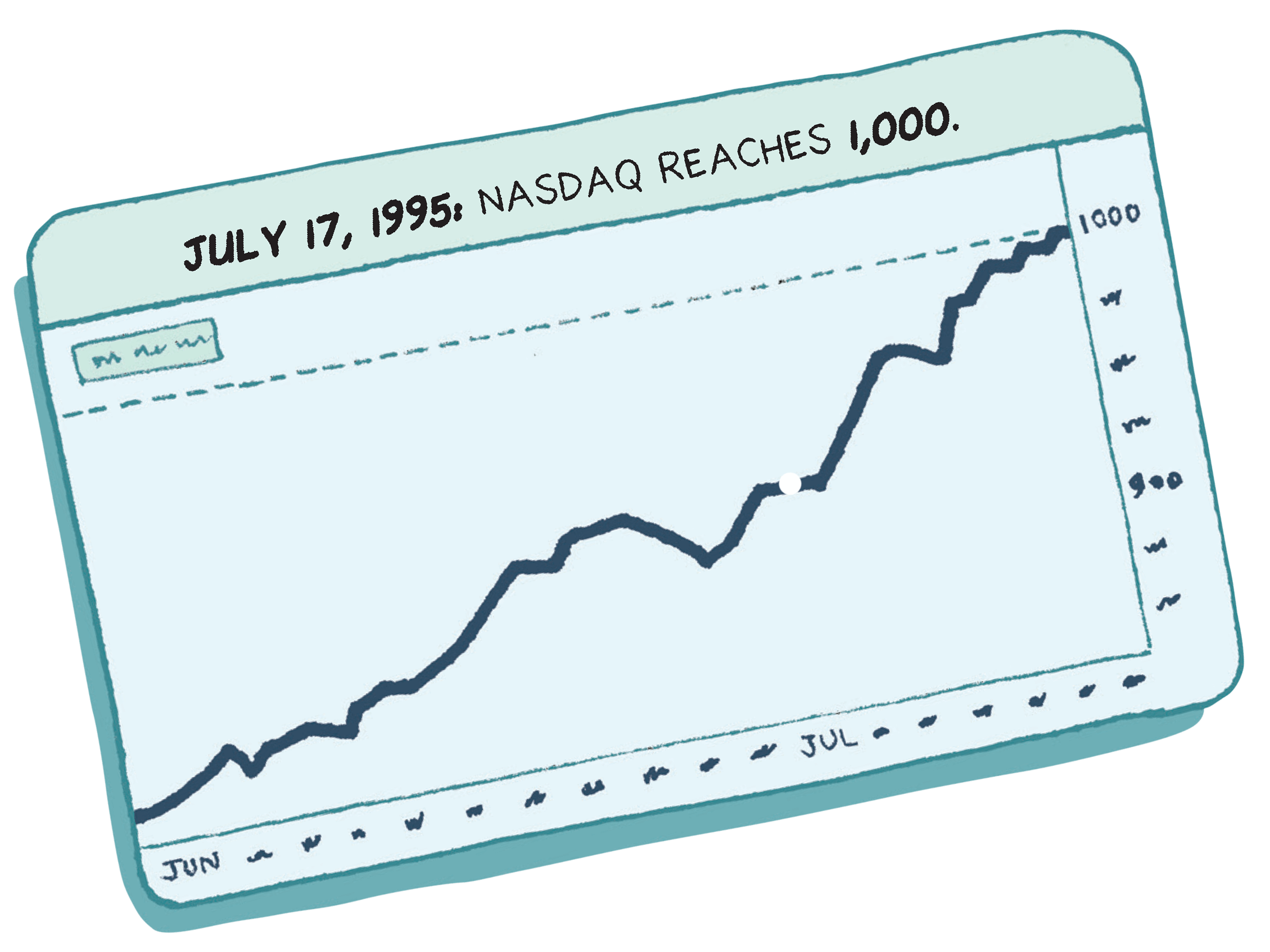

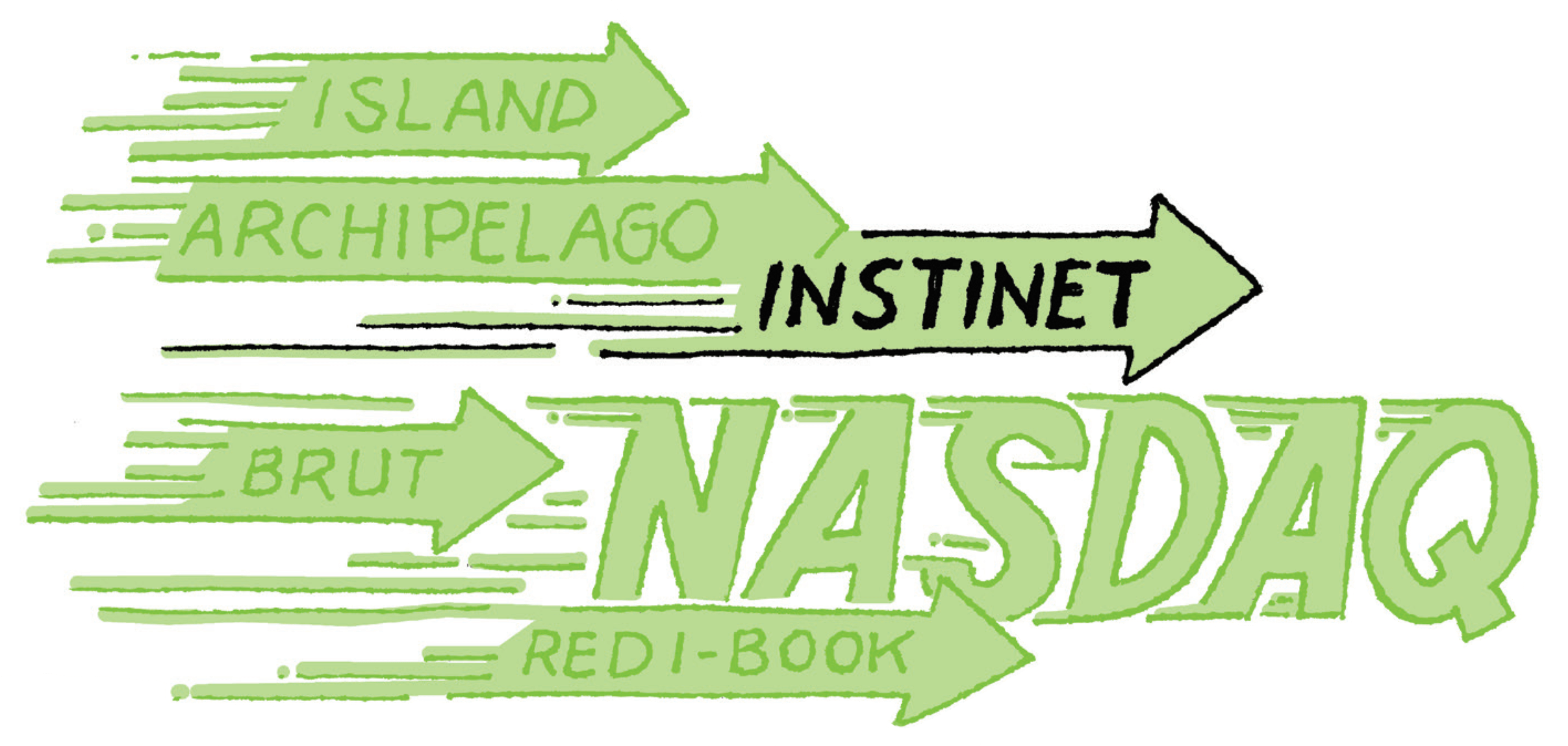

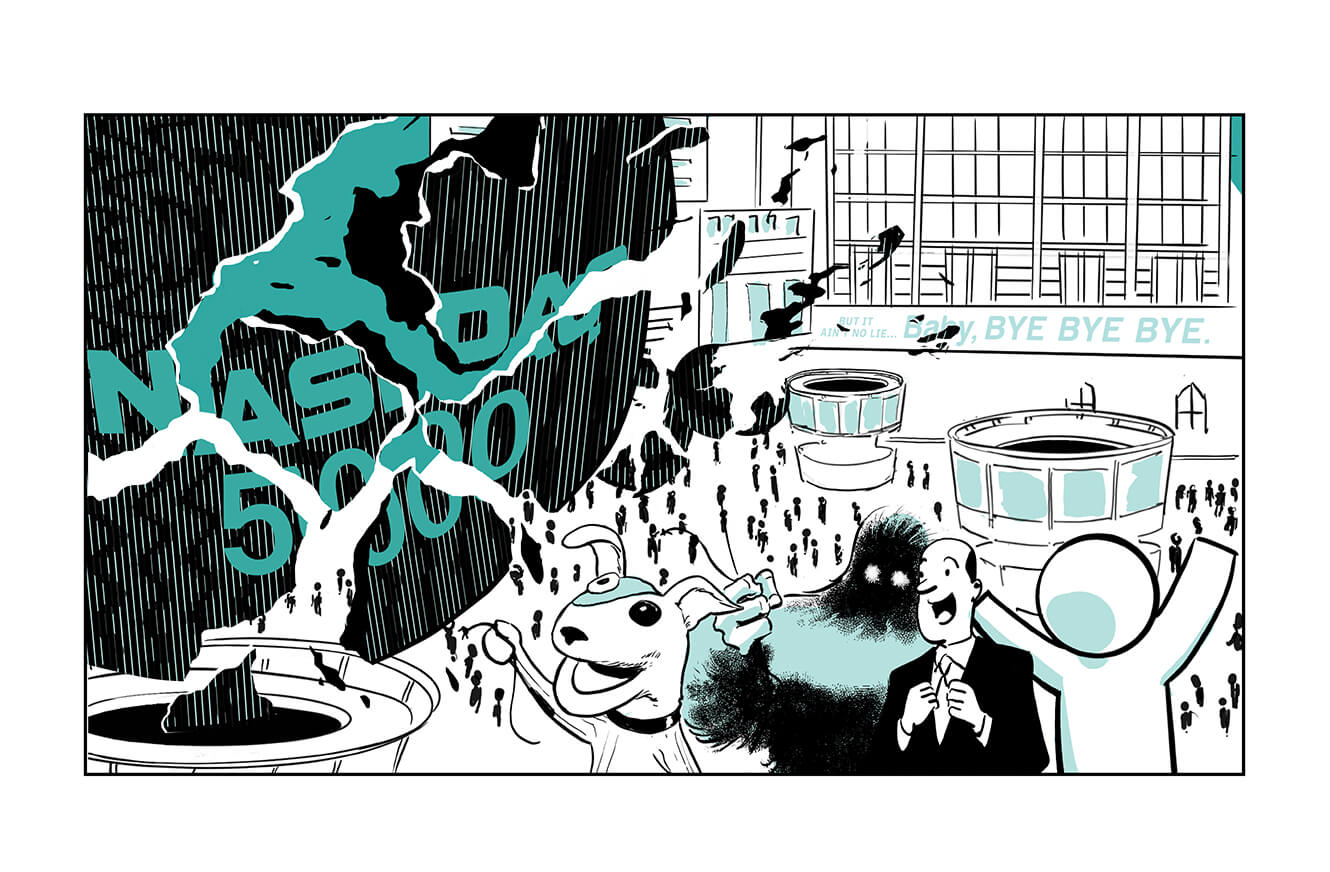

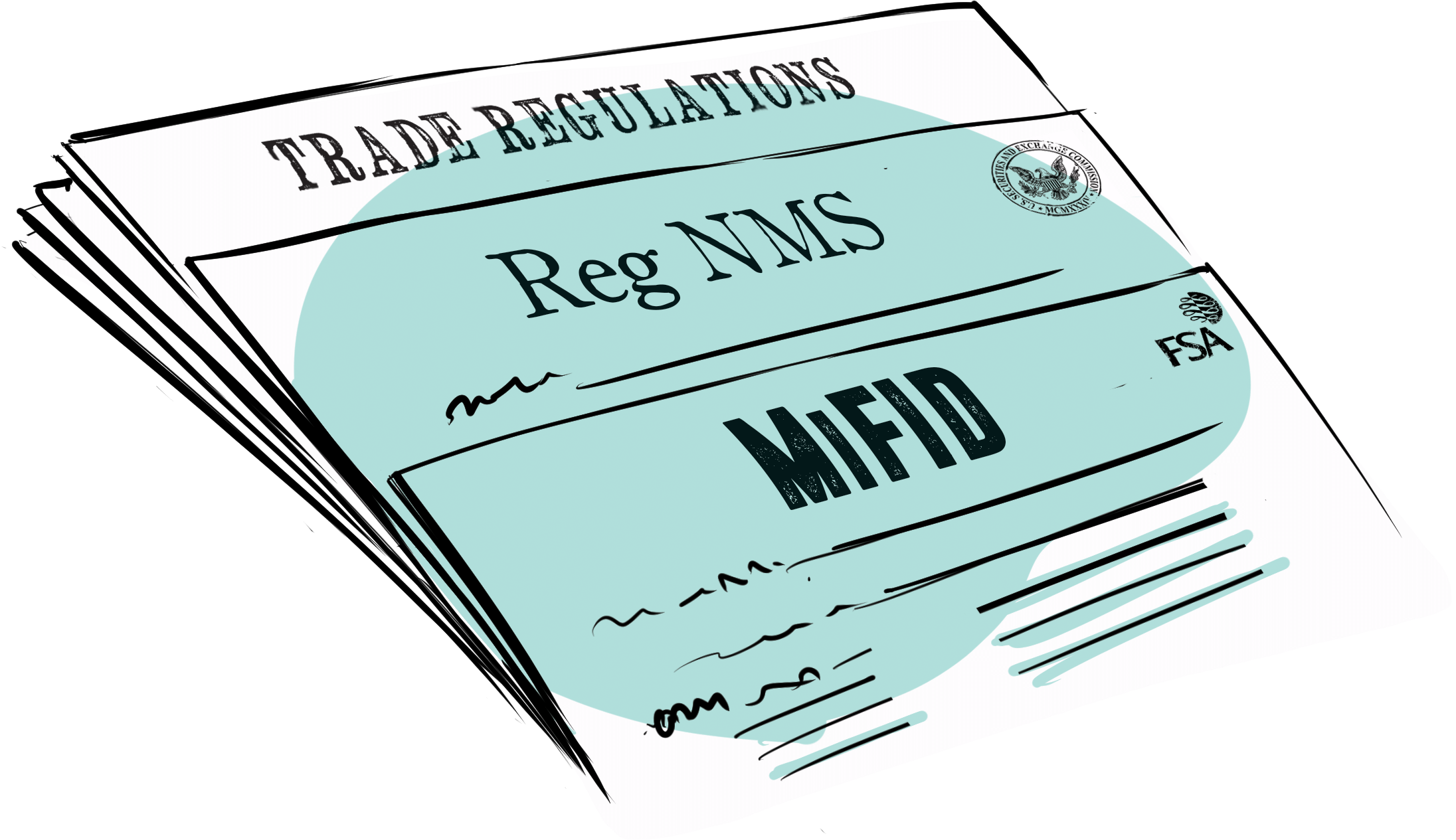

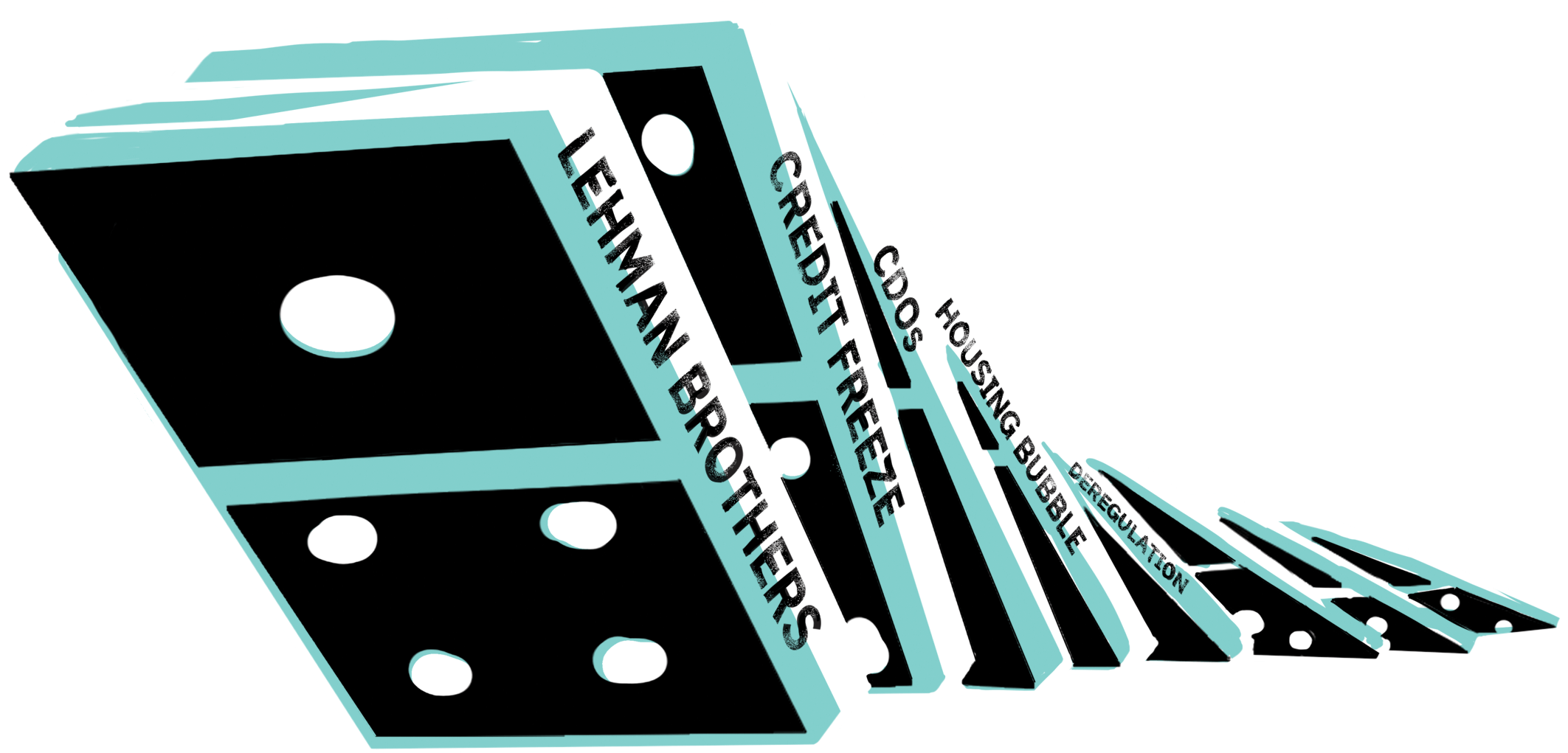

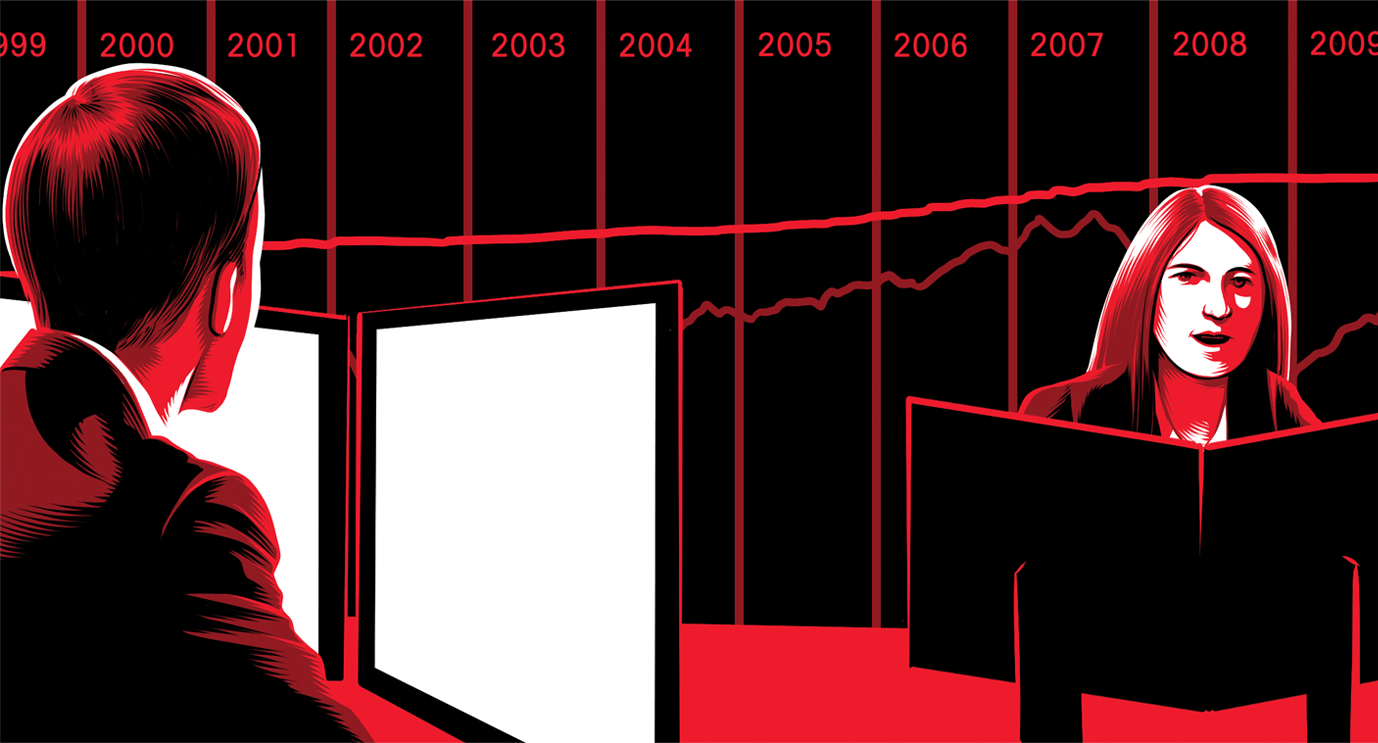

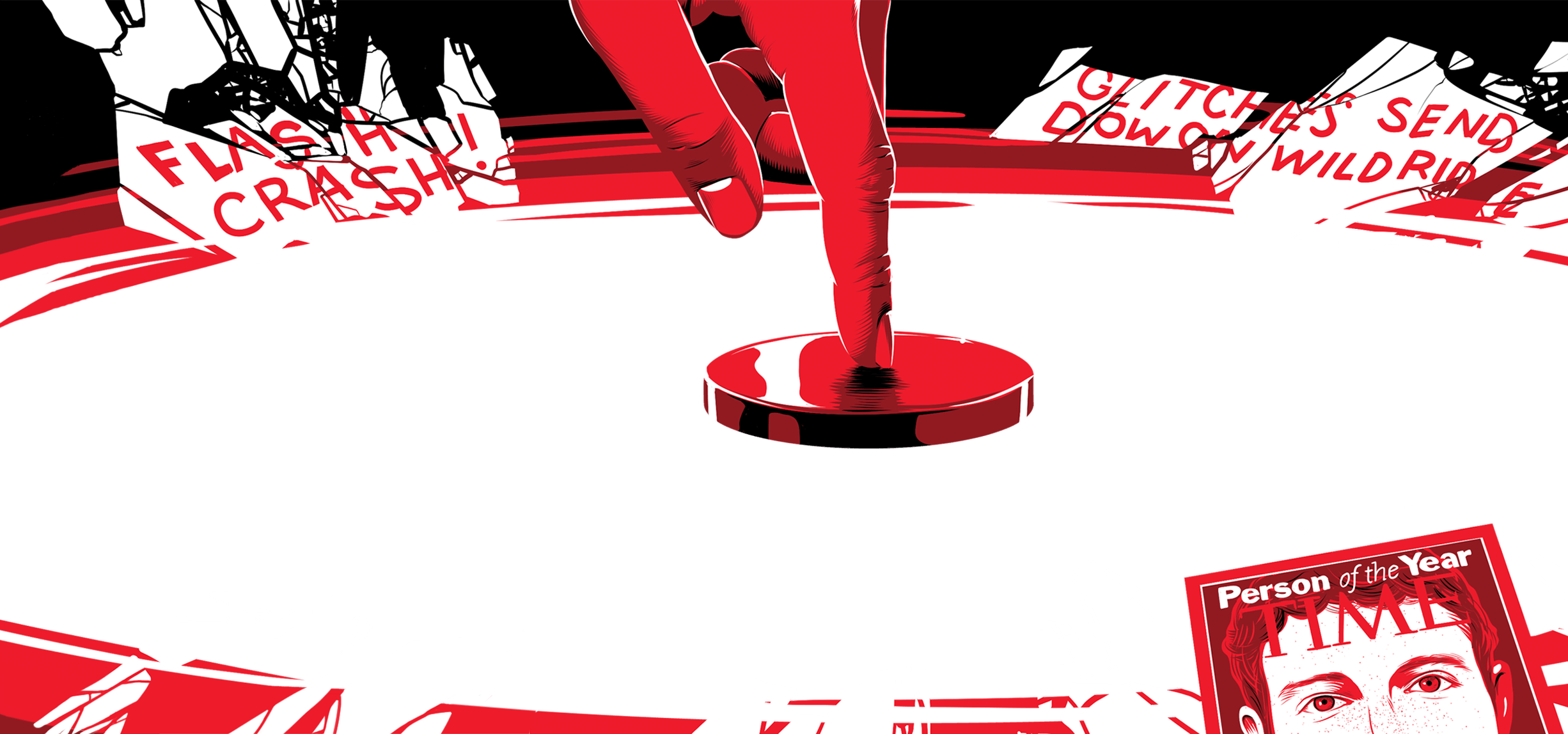

Eventually, these ideas about electronification and disintermediation reached a critical mass and gathered enough momentum to break the inertia of hundreds of years of business as usual. Like many evolutions, it was often propelled forward in giant leaps by external, dramatic events. Finally, it became clear that an accessible, transparent, and efficient electronic marketplace could bring innumerable benefits to the industry, the economy, and individuals everywhere.

It wasn’t always easy for the people who labored to make Instinet successful over the decades. They faced tremendous headwinds. The firm made strategic decisions—time and time again—to position itself exactly where the industry and its clients needed to go. Sometimes it was serendipitous, but most of the time it was because the leaders who have driven Instinet forward over the years have all embraced the pioneering spirit that inspired the firm’s original founders. They discovered that challenging the status quo can be habit forming; it can become an integral part of an organization’s culture.

Of course, no company exists in a vacuum. The influences that shape an enterprise come from without, as well as within. Over the last fifty years, we have seen dramatic changes in the global geopolitical landscape; in the role and evolution of technology; in the economic environment, the markets, and the regulatory structures that govern them; and in the world’s people—our cultures, our societies, and our lifestyles. So it would be impossible to chronicle the history of Instinet, and of the existing state of fintech, without taking all of these critical factors into consideration.

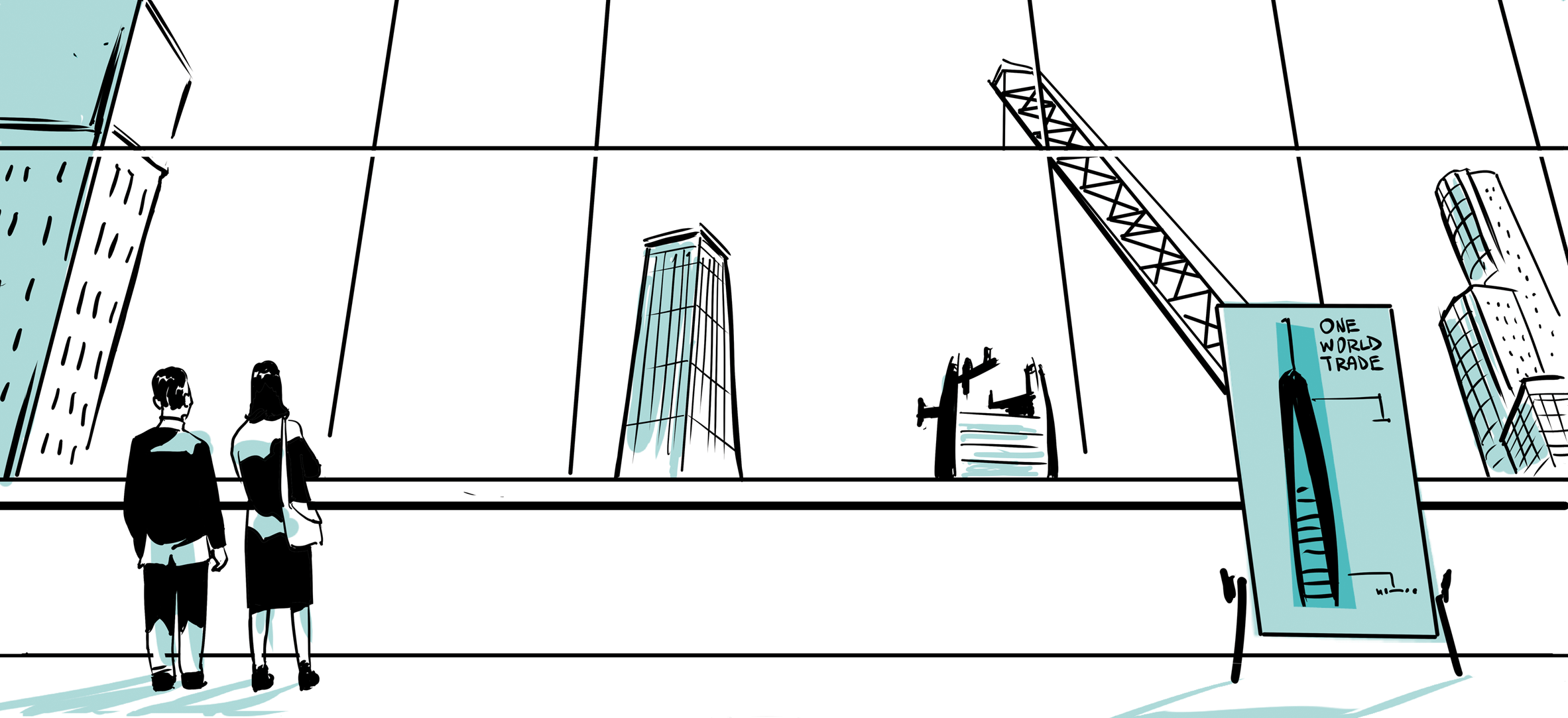

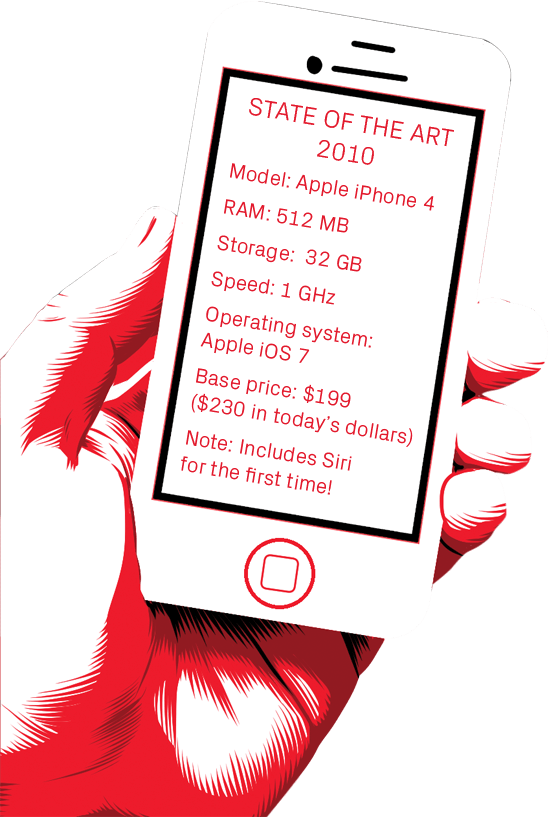

When Instinet’s founders sketched out the first schematics of their electronic network, they knew it was a game changer. They saw the extraordinary potential of a simple premise: connecting people with information, and with each other, to trade more efficiently. Technology was the medium that made it possible. What they probably didn’t foresee was how profound the electronic transformation of the markets would become. Or how technology would—and still does—relentlessly push us forward, continuously expanding the limits of what’s possible.

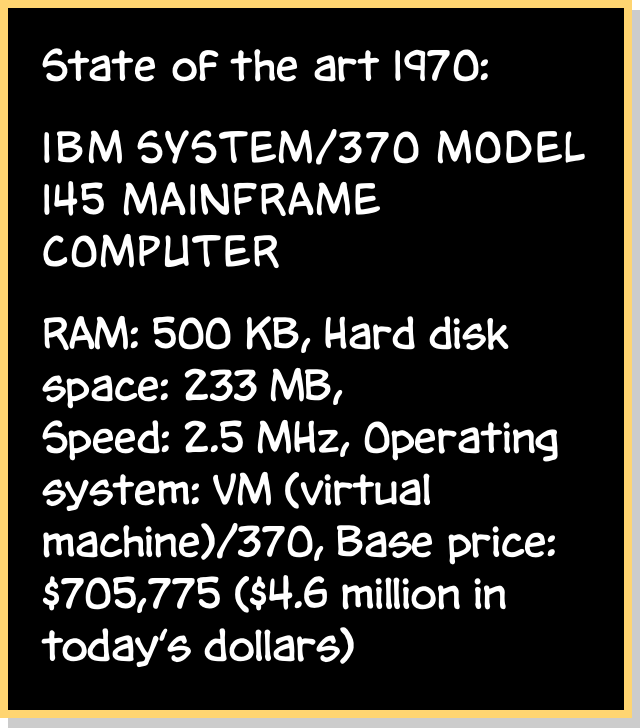

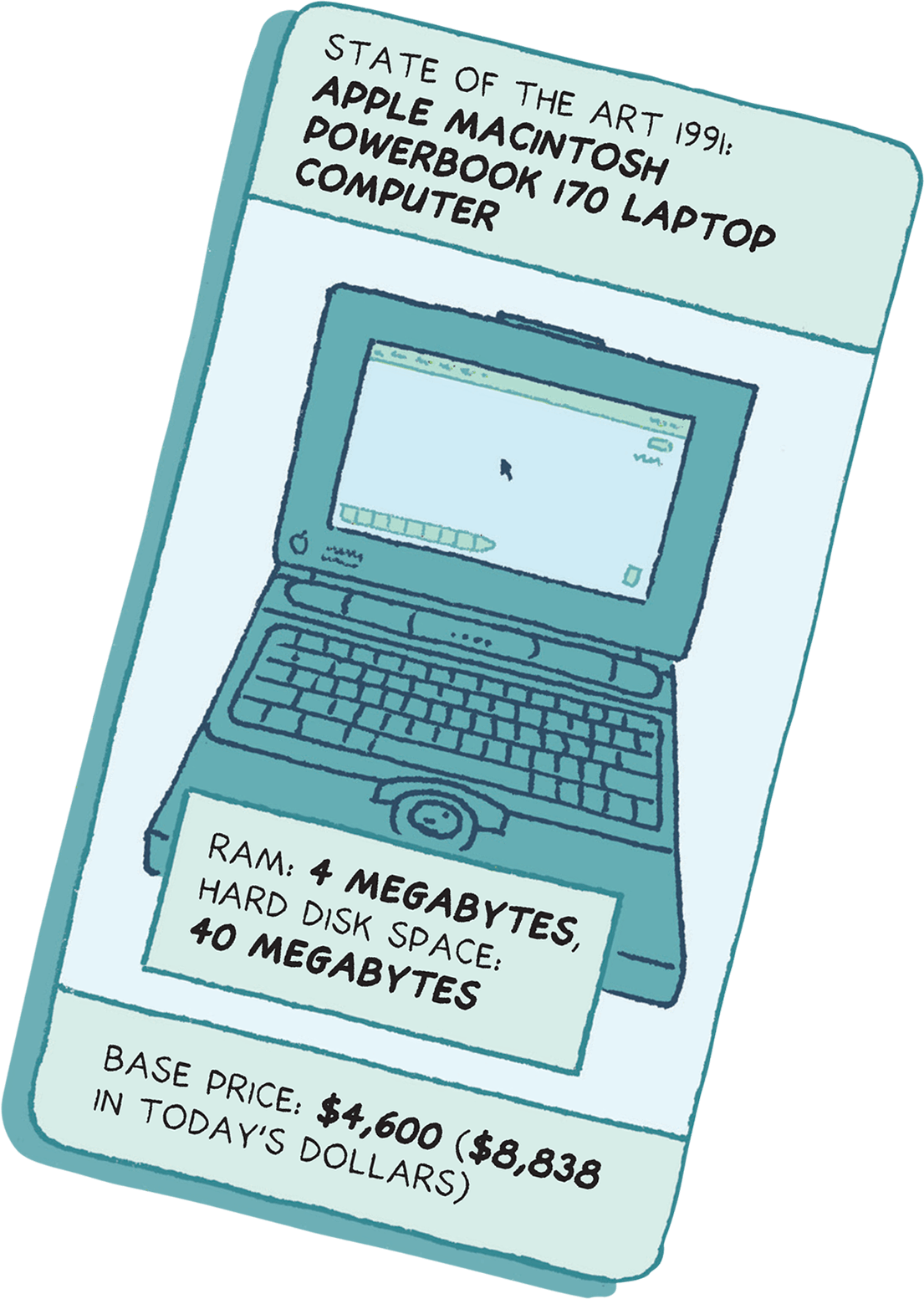

When we think about what’s next for the financial markets, we can try to track and anticipate technological breakthroughs: advances in big data, machine learning, artificial intelligence, quantum computing, the Cloud, and distributed ledgers. Even virtual reality. But in another fifty years, these may all seem as quaint as the mainframes, punch cards, and teletypes of 1969. So perhaps there’s another way to think about what’s next—to focus on what’s constant, rather than what’s changing.

This brings us back to our original premise: connecting people with information and with each other to trade more efficiently. When you look past the awesome complexity, speed, and scale of today’s global financial markets, this remains the essence of what we do.

It also brings us back to human ingenuity: the inspiration and hard work of people like Pustilnik and the community of innovators who built upon his ideas and took them farther than he may have ever imagined.

It is this kind of relentless intellectual curiosity, the willingness to anticipate and bring about change, and the philosophy of innovating for the real needs of the market and its participants that will define and create what comes next. It always has, and it always will. So while the technologies of 2069 may exceed today’s wildest dreams, that’s one prediction we are willing to stand by.

“Instinet’s greatest legacy is that it proved that low prices, low commissions, and frequent, fast, and anonymous trading were entirely possible. That has become second nature to many traders.”

Jerome Pustilnik, Founder & CEO: 1969 – 1984

“It was an uphill struggle to be first. Being the first is always more painful than being second. A lot of these innovations were probably going to happen anyway. They happened sooner because Instinet did them.”

David Manns, Chief Systems Architect: 1971 – 2002

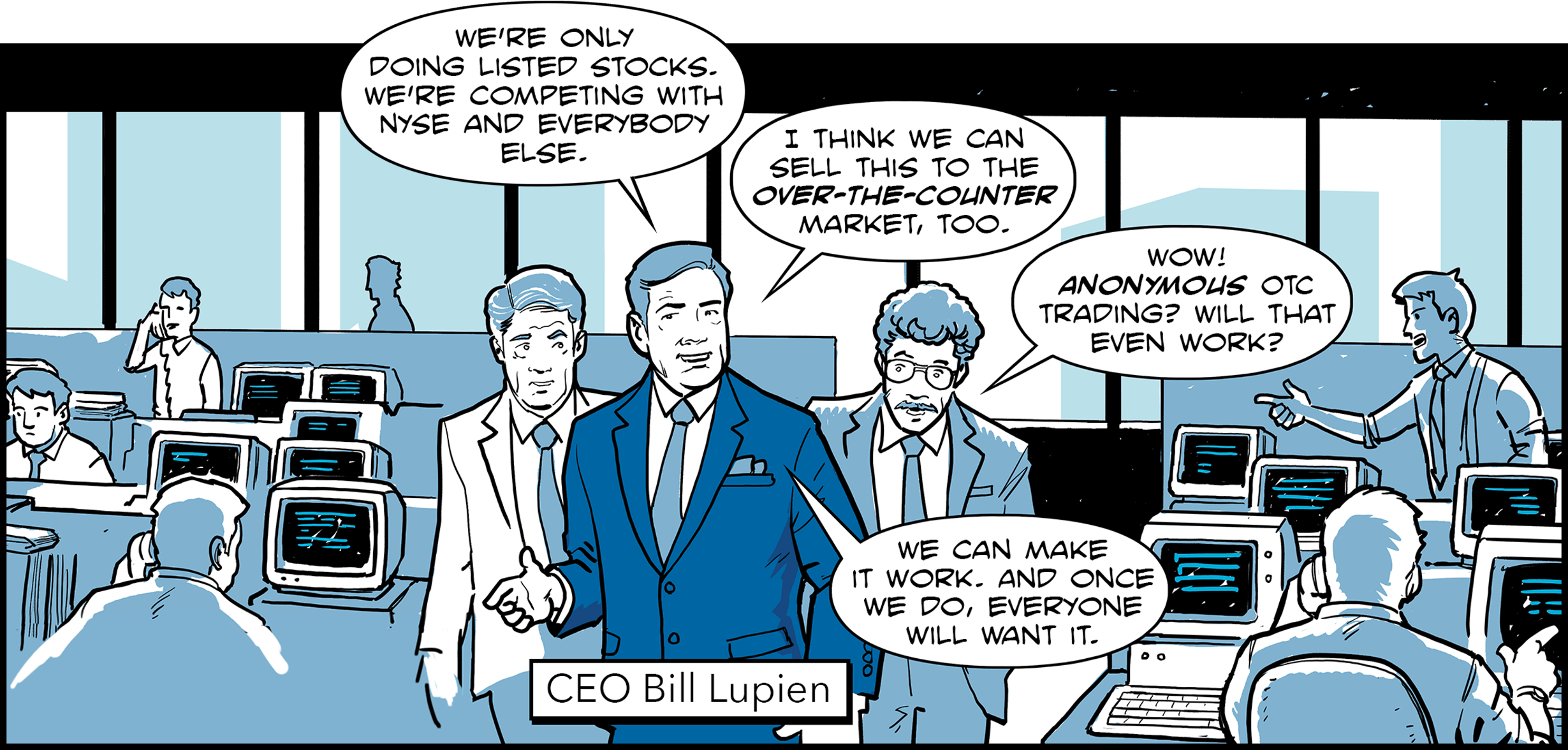

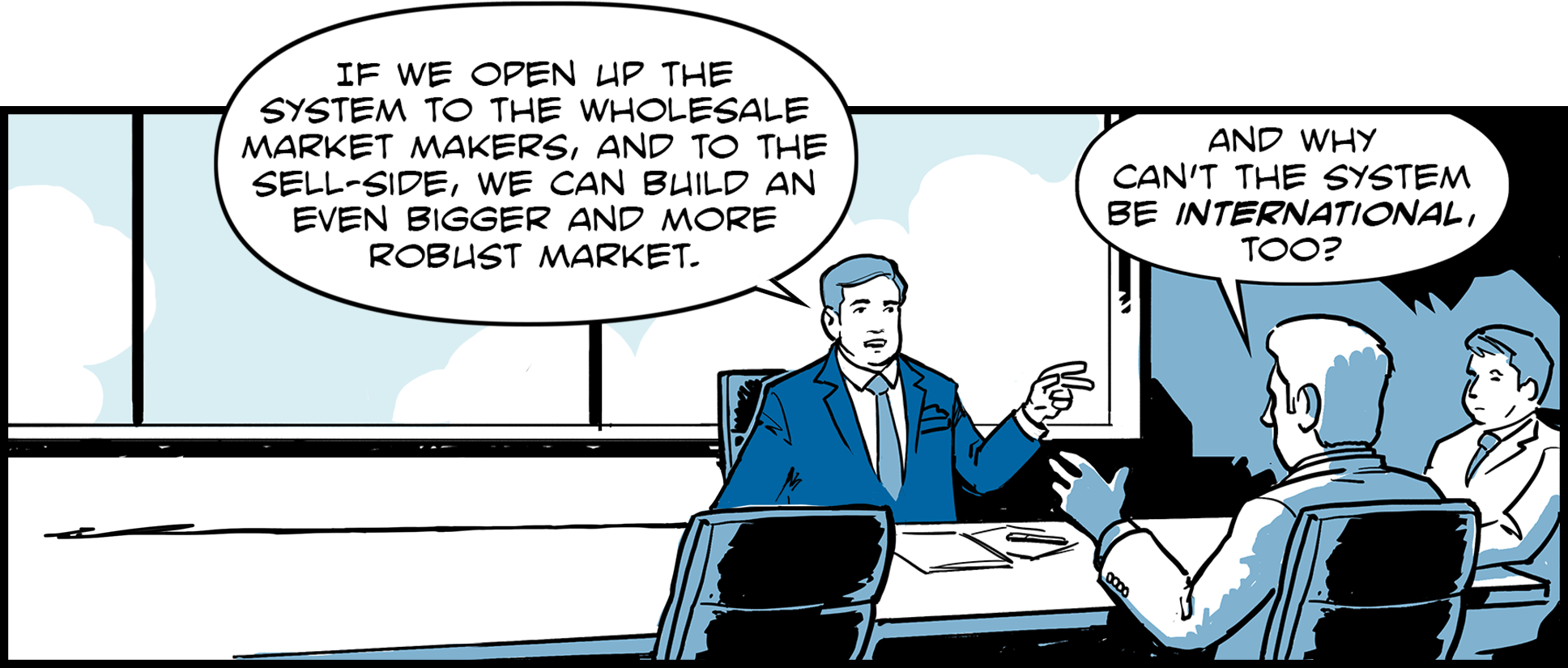

“It’s hard to trade a stock when you don’t know the price and if you bought or sold it. With Instinet, they enforced the audit trail. Everyone knew the price and whether it was bought or sold. As volumes started to explode, Instinet opened the eyes of a lot of people.”

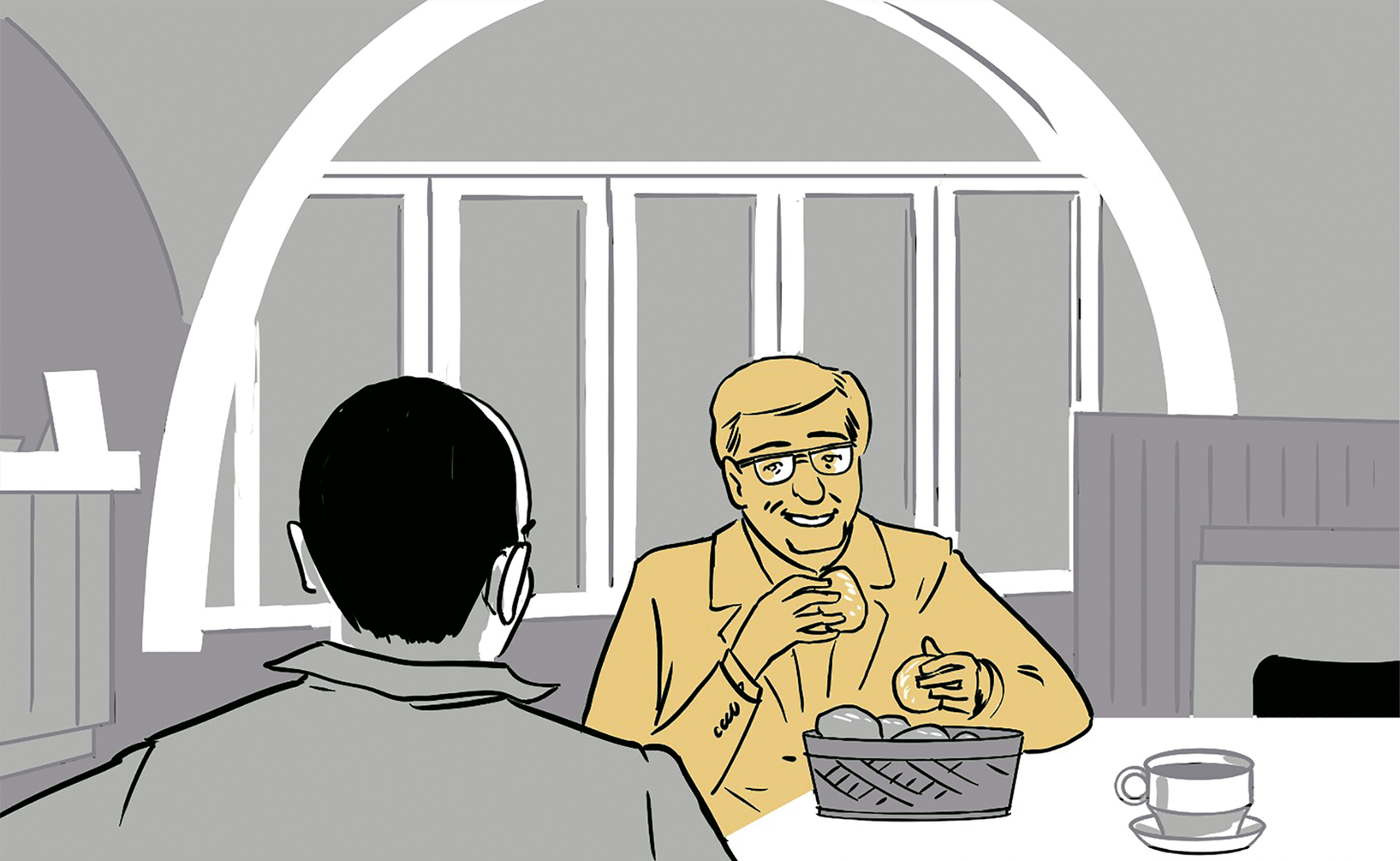

Bill Lupien, CEO: 1984 – 1988

“My time at Instinet is the best time of my career. Best job I have ever had. Best people, best time. We created technology people didn't think would be possible.”

Michael Sanderson, CEO: 1991 – 1998

“We brought in a lot of young, brilliant technologists. The triumph was getting them to wear a shirt with a collar on it. They would always forget to wear a tie when meeting with clients. These were the kind of people that were flying drones around the office when no one knew what a drone was.”

Ed Nicoll, CEO: 2002 – 2006

“Instinet always had a strong culture of doing the right thing by its clients. It’s always had, and it still has, great people working for the firm who are passionate about the business. And are constantly innovating. That’s a pretty good recipe for success.”

Doug Atkin, CEO: 1998 – 2002

“So many of the ideas that Instinet has and continues to put in place are from conversations with clients—what they are looking for, how they can improve their execution quality and overall trading process. Clients have a good appreciation of what Instinet can do for them. And they want to see how the firm continues to innovate, so they want to stay involved.”

Jonathan Kellner, CEO: 2014 – 2018

“Instinet’s DNA is about fostering innovation and being part of the market’s evolution. I look forward to the next phase of Instinet’s remarkable story as we break new ground and make new history.”

Ralston Roberts, CEO of Instinet